The Russian Jewish artist Anatoly Kaplan (1902-1980) came into our lives the same way my siblings and I discovered all art—through the works that our mother Masza Roskies purchased and displayed in our home. But how would she have acquired Kaplan’s art? In the 1960s we lived in Montreal, Canada, and the artist was behind the Iron Curtain in Leningrad. How, then (as Yiddish would ask), did the cat cross the water?

Our mother was a lover of the arts and a patron of artists. In Montreal’s Jewish community, this meant supporting the work of Yiddish writers and local Jewish visual artists like Alexandre Bercovitch (born in Odessa) and his daughter Sylvia Ary. In the same vein, our mother’s friendship with the poet Melech Ravitch led her to the work of his son Yosl Bergner, who had illustrated many stories by the Yiddish writer I.L. Peretz.

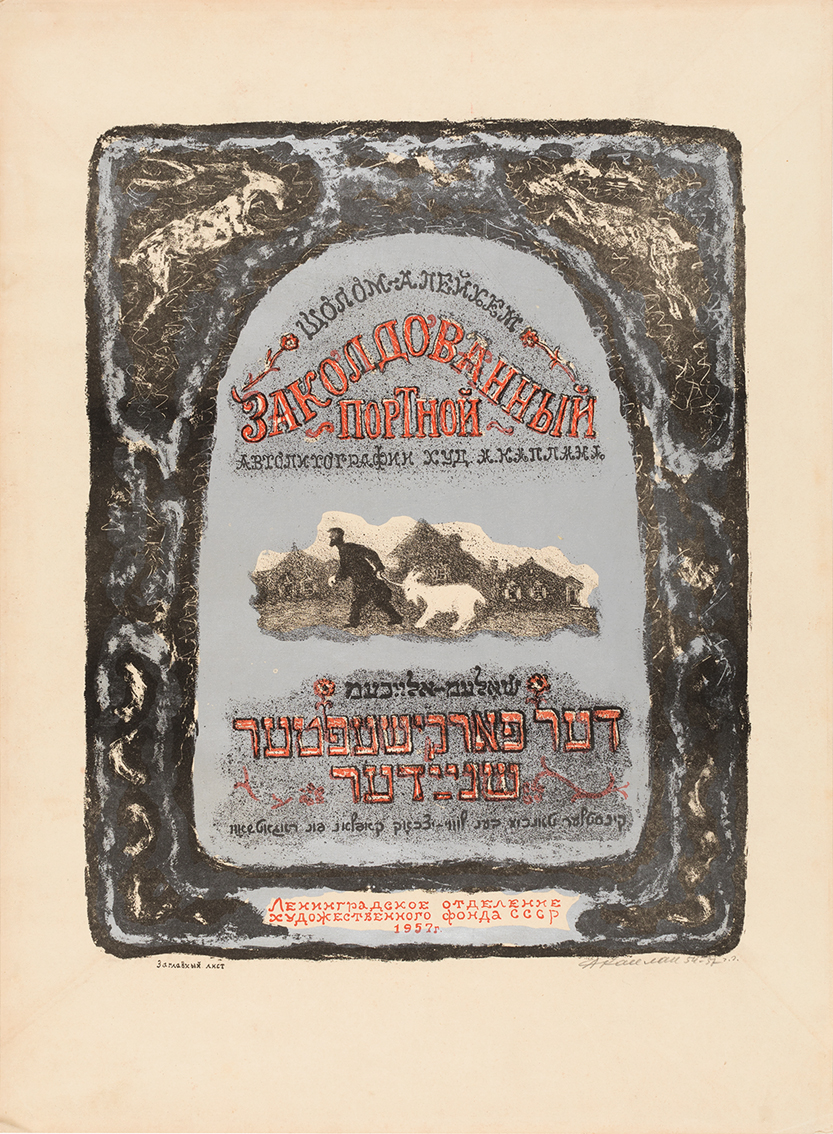

To be sure, the Montreal Jewish community was plagued by deep political divisions—nothing unique, there—but these did not necessarily affect cultural appreciation. When a local Jewish Communist began to import and sell the works of artists in the Soviet Union, Mother looked beyond the ideology of the seller to the merit of the wares. In particular, she was enchanted by Anatoly Kaplan’s lithograph series of illustrations for Sholem Aleichem’s story, Der farkishefter shnayder, “The Enchanted Tailor”—so much so that she bought several sets for herself and her children. By the time my brother David Roskies and I became professors of Yiddish literature and were teaching this story, we were displaying Kaplan’s images in our own homes.

I had loved these pictures from the moment I first saw them, but it was years before I began to think about what might have prompted the artist to undertake this major project. The Bolsheviks had early on outlawed the practice of Jewish religion and even more so Zionism, the movement of Jewish self-emancipation. But there were dozens of ethnic minorities living in the USSR, and the regime was aware that it could not erase their national identities at a stroke. In the case of the Jews, Moscow supported Yiddish as a legitimate vehicle of Jewish self-expression—so long as it conformed with Soviet precepts.

Part of modern Yiddish culture lent itself particularly well to such use. Writers like Mendele Mocher Sforim and Sholem Aleichem, who poked affectionate fun at traditional Jewish life, could be safely studied as depicting aspects of the Jewish past. Dramatists adapted their works for the Yiddish theater, artists drew on their subjects and themes, and Jewish schools taught their stories. As their works were widely disseminated—also in Russian translation—they would have become familiar to anyone in the Jewish sphere of Soviet culture; editions accompanied by scholarly apparatus sometimes even smuggled in information about Jewish practices, beliefs, and texts.

By the time Anatoly Kaplan was creating “The Enchanted Tailor,” however, the fate of Yiddish culture had been fully decided and was fully known. Major figures of the Jewish intelligentsia had been executed as traitors. The once buoyant Yiddish theater was gone, its brilliant director Shlomo Mikhoels brutally murdered. More and worse terror would follow.

Kaplan was fifty years old when, finally, Stalin’s death in 1953 introduced a more lenient period, known as “the thaw,” which, although coming too late to save the victims, gave him more creative freedom than his predecessors had enjoyed. Seizing the opportunity, he turned to some of the best-known Yiddish fiction. Although the dealers who brought Kaplan to Canada certainly hoped his works would help rehabilitate Soviet standing among Jews in the West, the works themselves transcend the conditions that governed their creation.

Illustration was a highly regarded form of Soviet art, and Jewish artists had designed brilliant works for Yiddish publications. Kaplan, however, was not working to order, and his lithographs were not mere illustrations. He used them to retell the stories in a different medium for a new generation with no linguistic access to the originals. The way these works became part of our life thus helped to reforge the connection among Jews who had been long separated by geography and politics.

The Story

“The Enchanted Tailor,” first published as “A Story Without an End,” is Sholem Aleichem’s darkest work. The plot is taken from a popular Chelm tale, but readers expecting familiar comedy would have been all the more surprised by what he does with it.

In the folktale, a poor Chelmite is dispatched by his wife to a neighboring town, there to buy a female goat whose milk will help support their family. On his return trip, he stops for a drink at a tavern; mischievously, the barkeeper substitutes a billy-goat for the one he has come with—thereby earning the husband the ire of his wife when he gets back home and she tries to milk the animal. When the husband, now on his way to demand redress, again stops at the tavern, the barkeeper repeats his mischief in reverse. Turning up to complain of having been cheated, the husband is now treated by the seller to the inexplicably miraculous sight of his goat being happily milked. On his way back home, the sequence at the tavern is repeated, and then repeated once more, so that after a third failure the poor man takes his problem to the rabbis for advice. With the aid of Chelm’s famously irrational logic, the latter conclude their deliberations by pronouncing a general rule: whenever a milk goat is brought to Chelm, it turns into a billy-goat.

So much for comedy.

One could say that Sholem Aleichem radicalized this story. His clueless hero Shimen-Eli is a patch tailor, the lowest on the tailoring rung of the economic ladder. But he is also an ardent protester, one who confidently takes the side of the poor and who rails against philanthropic do-gooders, rabbis, and religious functionaries as “a gang of thieves and liars, deceivers, killers, gangsters, highwaymen—may the devil take them….” In Zolodoievke, Sholem Aleichem’s version of Chelm, one thus catches a whiff of the revolutionary spirit then laying hold of Russia: indeed, toward the end of the story, the town’s craftsmen take up the cudgels for their wronged colleague and resolve to go off to Kozodoievke—“Goatstown”—to avenge him, shouting, “Shears and irons: the people!”

To boot, our traditional Jewish hero is also president of the tailors’ synagogue, and with his tolerably good voice he often leads the prayers. They call him Shimen-Eli shma koleynu—Shimon-Eli “Hear Our Voice”—simultaneously a refrain addressed in the prayer book to God and a sly dig at his eagerness to “get at the podium.” As Shimen-Eli loves quoting Jewish sources, the story is also filled with snippets of Torah and liturgy. The narrator (that is, Sholem Aleichem) likewise partakes of this spirit, sometimes quoting Hebrew phrases followed by their Yiddish equivalents in faux-pedantic mimicry of the traditional method of teaching Torah: “Ish hoyo be-Zolodoievka, there was a man in Zolodoievka”; “veyavoy, and he arrived,” etcetera. Not coincidentally, these phrases echo the Book of Job.

And speaking of arriving: when our hero arrives in Kozodoievke, Reb Chaim-Chono, husband of the goat-keeper Teme-Gitl, is in the midst of teaching—what else?—a passage from the talmudic tractate “Damages” about the goat that, “when it saw there was food on the top of the barrel . . . leaped toward that same food.” These Jews consort with goats in theory and with goats in practice, yet they still do not appear to know the first thing about goats.

Sholem Aleichem delighted a readership that could appreciate both the connections with tradition and the departures from it. None other than Satan the tempter has coaxed Shimen-Eli into stopping for a tipple on his way home, and it is Satan’s human instrument, Dodi the barkeeper, a cousin of Shimen-Eli, who exchanges the goats. Shimen-Eli thus merits a little of his punishment because he has humiliated his cousin by showing off his own supposedly higher learning. In literature, a townsman should never belittle a country cousin, a Jew should never get too cocky, and Jewish wives like Tsippe-Beyle-Reyze might elicit more sympathy if they did not turn on their hapless husbands.

If these are just some of the themes that attach to our hero’s misadventure, Sholem Aleichem’s most decisive change to the Chelm story was to remove the very thin line separating comic foolishness from its tragic consequences. The resolution of the story, which takes no more than a sentence in the Chelm version, here extends for the last five of the story’s thirteen chapters, during which Shimen-Eli loses his hold on reality and descends into madness. Everything spins out of control. The tailor imagines the goat must be a gilgul, the transmigrated soul of some wronged dead individual, a belief that is reinforced by a local barkeeper. The rabbis address an accusing letter to the goat-seller that elicits an equally passionate response from Goatstown, rousing Zolodoievke’s fellow artisans to leap to their colleague’s defense by threatening to march on Kozodoievke, thereby escalating the confrontation between the two communities.

A doctor who is called in to tend to poor Shimen-Eli bleeds him to the point of possibly causing his death. His wife Tsippe-Beyle-Reyze and their children begin the mourning period even before they are widowed and orphaned. From having started out as a joyous and spirited community leader, Shimen-Eli dies in great loneliness despite all the hubbub around him—at which point the goat that has been dogging his footsteps breaks free and escapes.

Sholem Aleichem could not finally rescue his broken hero. Adored by his readers for creating “laughter through tears” or, more accurately, laughter through fears, he admits his authorial failure, telling the reader, “You know me, and you know I prefer cheerful stories. . . . [M]oralizing is not my style.” Instead of an ending, he advises: “Laughter is healthy. Doctors prescribe laughter.” These words became a popular Yiddish byword, to be used in extremis when events are anything but funny.

The Album

Whenever an artist creatively appropriates the work of a predecessor, he enriches its value. Just as Sholem Aleichem had transformed a folktale into literary fiction, so Anatoly Kaplan, whatever may have originally inspired him to create a lithographic edition of this story, recast it in visual form.

This was not purely an act of homage, and it was not in the least nostalgic. By this time, the world of Sholem Aleichem had itself been utterly and cruelly obliterated. Kaplan now proceeded to turn Sholem Aleichem back into the world of previously iconic folk imagery. If the writer had brought Chelm up to date, the artist gently pushed it and him farther back in time.

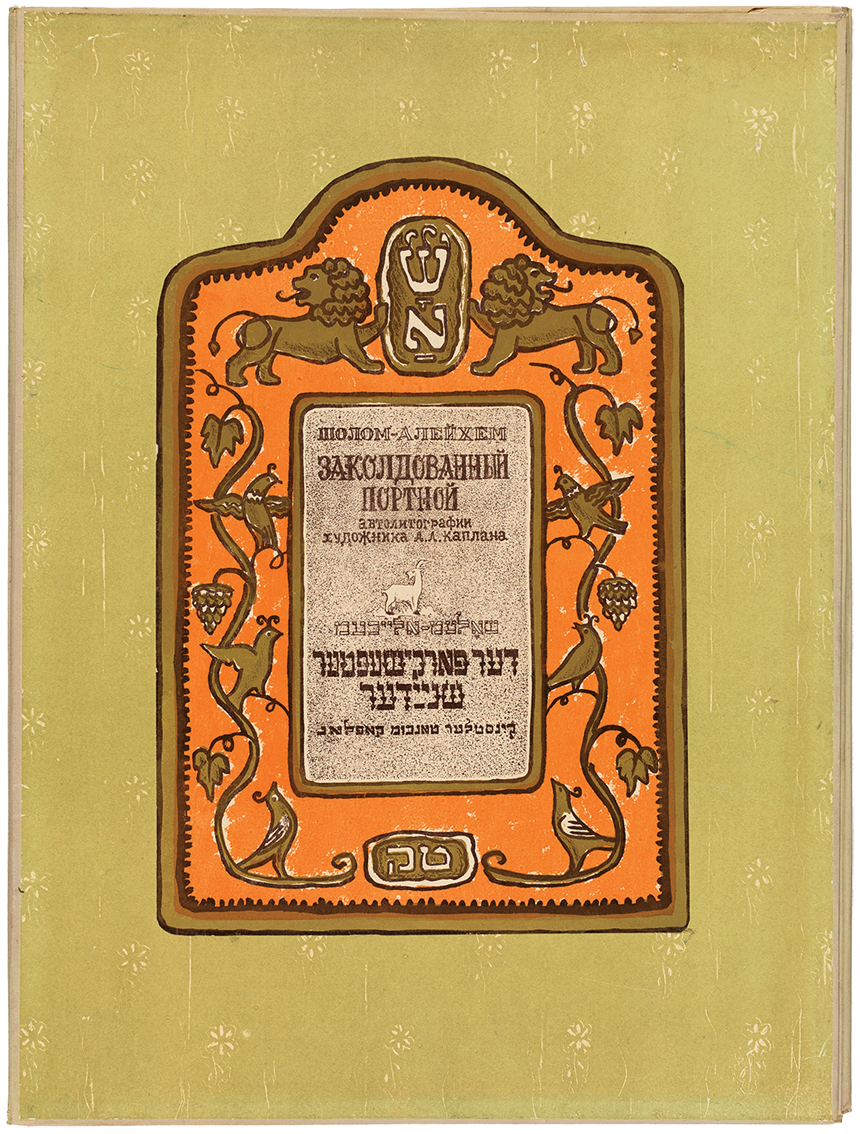

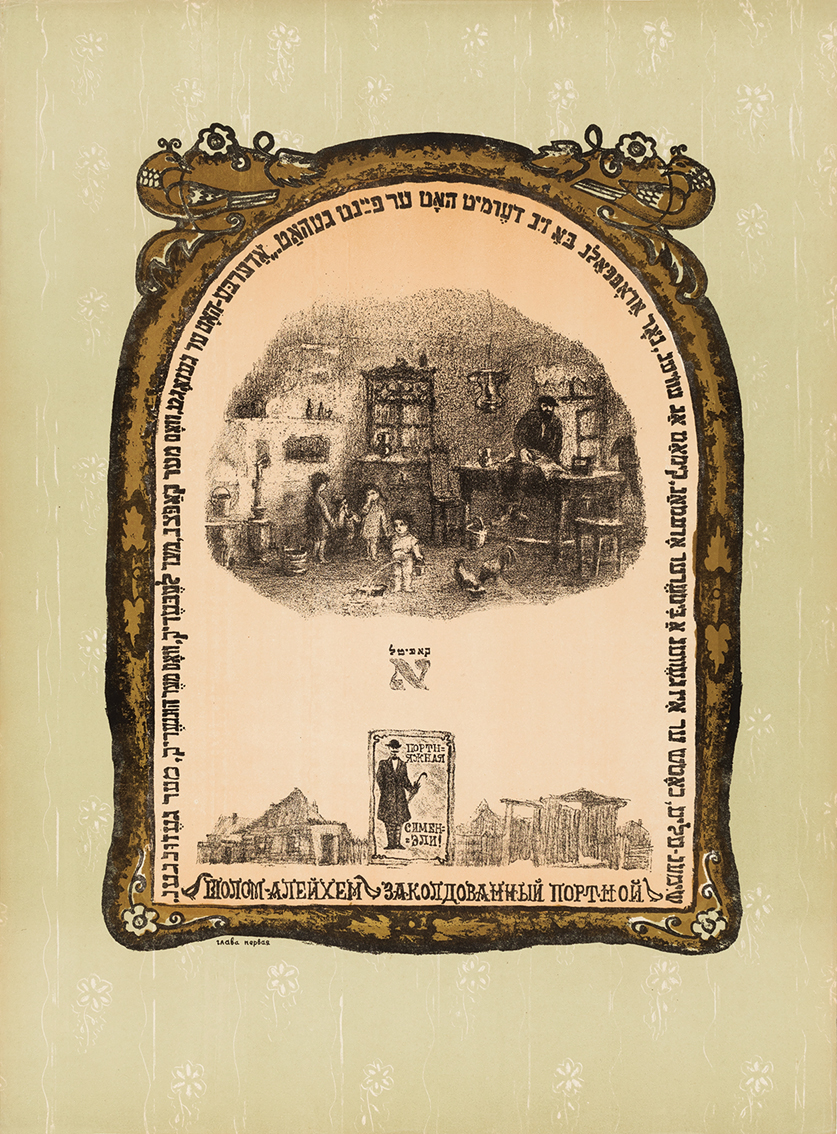

How? Sholem Aleichem had greatly enlivened folk comedy with his jabs at the retrograde aspects of shtetl life, with dialogue that could easily be transposed to contemporary situations, and with invective intended for current circulation. Kaplan, registering the pastness of the past, frames his work as an album, each image decorated in designs that evoke the folk art of Russia’s wooden synagogues. Readers encounter persons who lived in an altogether different age, with different customs and costumes, speaking a different language, and requiring an old-fashioned style of art to tell their story. Rather than inviting our identification with our ancestors, Kaplan acknowledges the gap between ourselves and those who are definitively no longer with us.

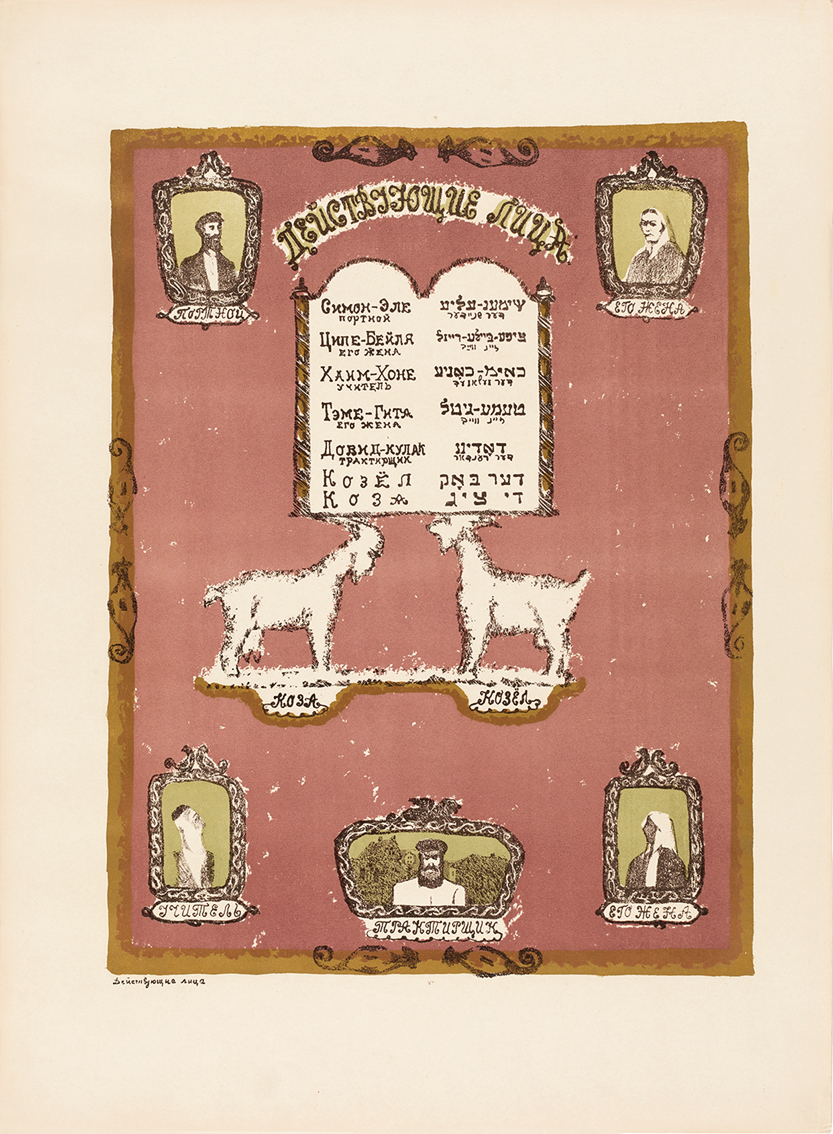

Thus, in addition to the traditional presence of lions and birds on both sides of a Torah ark, and in keeping with the story’s main motif, Kaplan gives pride of place to images of goats. In Judaism, the goat figures preeminently as a sacrificial presence in a ceremony of atonement for collective sins. Sholem Aleichem’s story inverts this by making the death of Shimon-Eli the vehicle for the goat’s release—he is now the atonement, while nature’s creature runs free.

Kaplan picks up on this visually by including his goats, frolicsome and ubiquitous, in a cast of characters who include the Zolodoievke couple Shimen-Eli and Tsippe-Beile Reise, the white-bearded teacher Chaim Chone with his equally stern spouse Teme-Gitl, and Dodi the hefty keeper of the wayside tavern. He also gives us not one but two facing male-and-female goats as if to say: just because Shimen-Eli doesn’t recognize the difference between the sexes, I do. Lastly, the frame around the visual field is filled with the running Yiddish text of the story itself: a verbal “handbook” or guide to the pictorial action within.

As told by the artist, the story begins in cheerful poverty. Shimen-Eli is first seen standing at his worktable while at the center of the picture one of his littlest children is happily peeing into a chamber pot. Art-lovers will catch the visual allusion to Michelangelo’s David, and all viewers will enjoy the pleasure children take in their bodies before inhibitions set in.

But this also introduces the theme that will lead the tailor from comedy to madness and death—namely, his blindness to nature. Boys pee one way; girls, like presumably the little sister in the drawing, another. Had their father been alive to such things, he could have distinguished between male and female goats and figured out the trick being played on him. His poverty cannot escape the bonds of necessity because it takes no account of the real world.

This silent critique of Jewish powerlessness perfectly suited the Soviet emphasis on material reality over religious teachings. One of Kaplan’s depictions of encounters between Shimen-Eli and the innkeeper is framed by the former’s prediction, enunciated in the page’s wraparound Yiddish text, that the rich who oppress us will soon get their due. But Kaplan simultaneously emphasizes that Shimen-Eli’s God-centered celebration of the world does not stand a chance against devious attempts to bring him down. The dark tavern rising in the middle of several pictures is a deliberately menacing image of what lures our hero to his fate. We never really see Sholem Aleichem’s jolly tailor setting out on his venture, brimming with self-confidence. Kaplan’s hero begins as a scrawny Jew and ends as the same scrawny Jew, only in the form of a corpse.

Our son Jacob Wisse, an art historian who grew up with these lithographs all around him, notes the striking contrast between Kaplan and his Belarussian compatriot Marc Chagall who, born fifteen years earlier, enlivened his impressions of the Jewish shtetl with vivid coloring and modernist technique. While Kaplan did the same in some of his earlier oil paintings and work in other media, here he made his art appear traditional and respectful of the literary work it illustrates. Chagall was intent on making Jews modern. By the time he undertook these lithograph narratives for so much wider distribution, Kaplan was commemorating a Jewry that was no more. Sholem Aleichem was still actively engaged with the society he was interpreting. Kaplan, for his part, knew that Jews in his time were being tricked or lured to their death just as Shimen-Eli was drawn into madness. His work is haunted by commemorative sorrow.

This brief account of a single lithograph album shows the need for more interpretive commentary on Kaplan’s rich body of work, especially on the part of those engaged in literature as well as art. Every work of his listed in this catalogue awaits its research and commentary. The changes Kaplan made to the Sholem Aleichem text, his excisions and emphases, the matchup between text and image, the possible “secrets” embedded in the arrangements and decoration—all these await proper attention and analysis.

Addressing other illustrative works by Kaplan, Jacob has noted their artistic modesty. The artist does not aim to compete with or overwhelm the text. Indeed, his subdued outlines of figures and forms, loose draftsmanship, broadly defined facial expressions, and soft focus as key elements come into view—all of these stylistic features suggest an artist who actively refrains from asserting too much, lest the visual overwhelm the written. One might ask, then, whether Kaplan was too respectful of writer and text, or was he instead drawn to a work that encouraged his overall approach? Almost certainly, the latter was the case.

The title of Sholem Aleichem’s story, “The Enchanted Tailor,” has also been translated as “The Haunted Tailor.” Kaplan himself seems to have been both enchanted and haunted by the subject. Enchanted he certainly was, as his work, however bleakly it must register some elements of the plot, feels like a happy artistic effort. All in all, his pictured story situates the Jew between the real circumstances of an overburdened existence and the thrilling promises of divine protection, with the latter orientation having contributed to a fateful lack of attention to the perils that lie in-between. In perfectly capturing the dire unyielding reality, the haunting sorrow, and the transforming enchantment, Kaplan follows Sholem Aleichem in refusing to leave us in despair. He was an ideal interpreter of this Jewish story without an end.

Ruth R. Wisse

Martin Peretz Professor of Yiddish and Professor of Comparative Literature, Harvard University emerita and is the author, most recently, of Free as a Jew: A Personal Memoir of National Self-Liberation

Also at Beit Avi Chai