Get to know Moses Mendelssohn – the philosopher who was also an accountant and a revolutionary, and remains a source of controversy to this day

In the XVIII century, the German-Jewish philosopher Moses Mendelssohn (1729–1786) was the most famous Jew in the world. His great fame earned him contradictory treatment: great admiration and identification with modernization on the one hand, and demonization and condemnation on the other. How did he become an early maskil (Jewish Enlightenment figure)? What were his confrontations with Christianity and with the rabbinic elite? What did his struggle for religious tolerance look like? Who was Mendelssohn and why is he an important figure in the history of modern Judaism? Here are some answers.

Rabbi or Philosopher

In his youth, Mendelssohn didn’t aim for a career as an internationally recognized philosopher – that wasn’t exactly in the cards for a young Jew in the first half of the XVIII century. He aimed for a career as a Torah scholar in the rabbinic elite. In 1743, following his teacher, Rabbi David Fränkel, he left his hometown of Dessau and moved to Berlin to advance his studies in Talmud and Halakha. At that time, this was the only respectable career possible for a talented Jewish boy.

The Autodidact Who Discovered Philosophy Through Maimonides

Mendelssohn’s horizons extended beyond the yeshiva world. He taught himself various languages – including German – as well as mathematics and philosophy. He first discovered philosophy through Maimonides’ book “Guide for the Perplexed,” and gradually became a German-Jewish philosopher.

A Double Life

Mendelssohn never held an academic position as a philosopher. To earn a living, he worked as an accountant in a textile trading house, and only in the afternoon and evening hours did he turn to writing his philosophical works. Both Jews and Christians came to his home, both rabbis and non-Jewish clergy, and the house became a sensation: a Jewish accountant who was becoming famous for his philosophical writings. At the same time, Mendelssohn was a devoted family man, father of ten children (six made it to adulthood), and an active member of the Jewish community and synagogue.

Founder of Modern Hebrew Press

In 1755, Mendelssohn published Kohelet Musar, considered the first Hebrew periodical in history. Mendelssohn sought to use it as a tool to stimulate public opinion on matters of ethics, society, and philosophy. Although the periodical was short-lived and only a few copies remain, it marked the beginning of the model of the modern Jewish intellectual speaking to the public without official rabbinic authority.

“The German Socrates” and the Breakthrough to Philosophy’s Summit

Mendelssohn gained worldwide fame for his book “Phaedon,” which dealt with proving the immortality of the soul in a Platonic style with modern adaptation. The book earned him the nickname “the German Socrates” and made him a valued member of the “Republic of Letters” – the transnational network of Enlightenment intellectuals.

The Friendship with Lessing

Mendelssohn cultivated a deep friendship with the philosopher Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, one of the central playwrights of the German Enlightenment. The two met in Berlin’s scholarly coffeehouses, where intellectuals listened to lectures, discussed current topics, drank coffee, played chess or billiards, and above all cultivated friendship, which was a central value in the world of their generation. Lessing even wrote the famous play “Nathan the Wise,” whose main character was inspired by Mendelssohn, depicting a dialogue between a Jew, a Christian, and a Muslim in Crusade-era Jerusalem, with the conclusion that there is no single true religion.

The Berlin Salon and the Confrontation with Lavater

Mendelssohn’s home on Spandau Street in Berlin served as an intellectual salon where Jews and Christians met. But this status also put him in tense situations. In 1769, the Swiss clergyman Johann Caspar Lavater, his conversation partner and one of the salon’s guests, sent him a public letter presenting an ultimatum: refute Christianity or convert. Mendelssohn was deeply hurt by the attempt to recruit him to Christianity, but this very injury strengthened his connection to his Jewish identity.

The “Biur” Project: A Bridge to German Culture

One of Mendelssohn’s most impressive and important projects was the “Biur Project” – a German translation of the Torah (in Hebrew letters) with modern commentary, designed to modernize Jewish education and bring readers from Yiddish to High German. It had two educational goals: Mendelssohn wanted to teach his children the Torah in a language they knew, German, instead of Yiddish. But beyond that, he saw it as a first step for Jews reading the Bible into culture, bringing the Torah closer to the language of high culture. The project aroused fierce opposition from conservative rabbis who feared its consequences.

The Struggle Against Religious Coercion and State Laws

Mendelssohn was a fierce fighter for freedom of conscience. He opposed the use of excommunication in the Jewish community and argued in his book that religion has no political authority and that religious authorities must not be given power to coerce. He called for separation of religion and state.

Hero or Villain

Mendelssohn remains a figure shrouded in opposing myths: some see him as the pioneer of modernity who saved Judaism from isolation, while others (mainly in Orthodox circles) see him as the villain responsible for the beginning of assimilation, especially since many of his children and descendants converted to Christianity. Either way, both sides agree that Mendelssohn was a revolutionary who took control of the world of knowledge from the rabbis and offered a modern Jewish alternative.

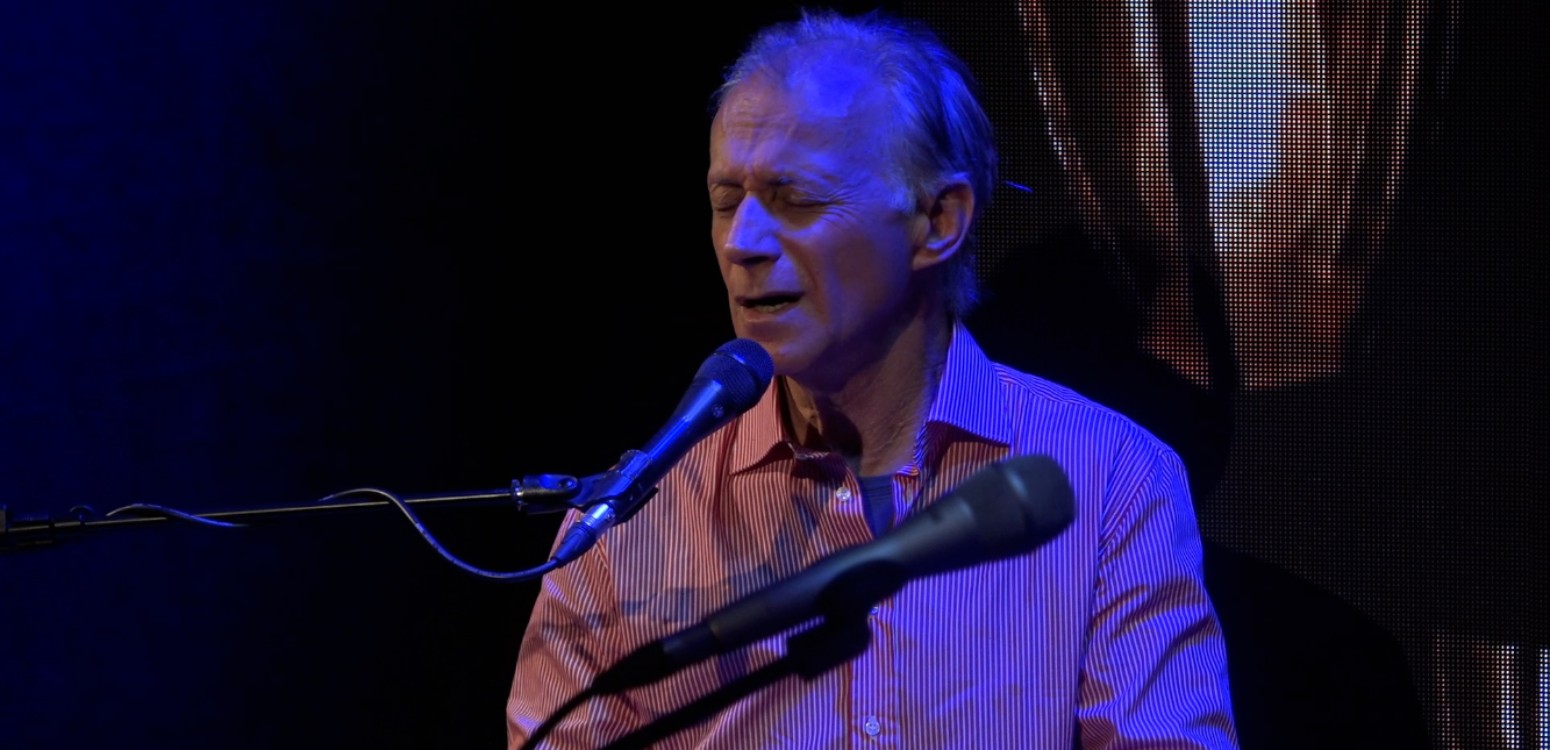

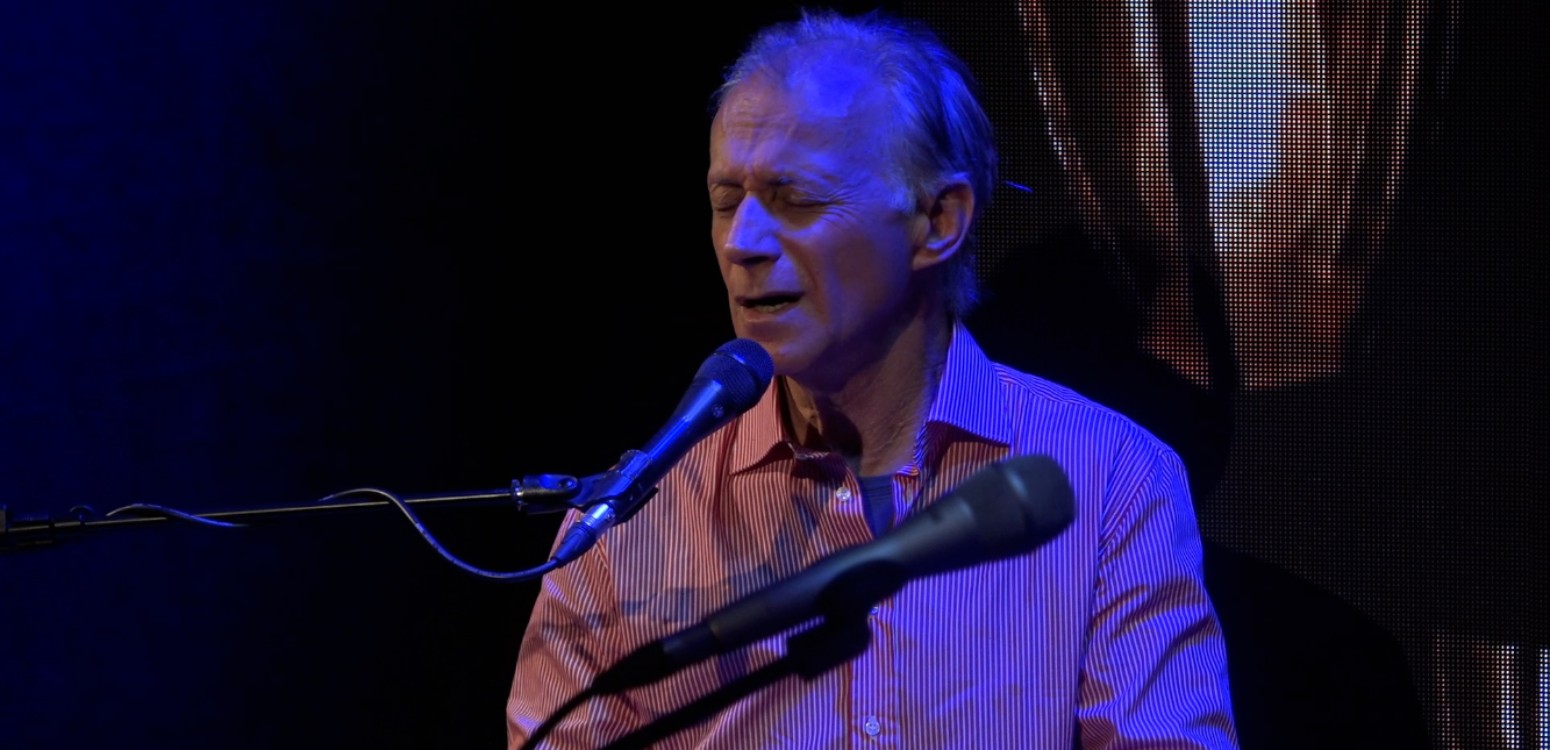

For more, see Prof. Richard Cohen’s online lecture on Moses Mendelssohn (in English).

This article was originally published in Hebrew.

Main Photo:Lessing and Lavater as guests in the home of Moses Mendelssohn.\ Wikipedia

Also at Beit Avi Chai