Anatoly Kaplan:

If I Forget Thee, Rogachov

David Rozenson

Remember, Leonid Osipovich, everything

will pass away – everything. Kingdoms

and thrones, wealth and millions of people – everything will perish. Everything will change.

Neither we, nor our grandsons will remain

and there will be nothing left of our bones.

But if our works contain even a grain of real

art, they will live forever.

– Lev Tolstoy to Leonid Pasternak

Prologue

I was first introduced to the works of Anatoly Kaplan in the early 2000s, in a friend’s apartment in a Soviet-era high-rise apartment building on Malaya Bronnaya Street in Moscow. In the entrance hallway, next to where we took off our shoes, there was a small lithograph in a plain black frame, depicting an elderly bearded man in a coat, one hand resting on a walking stick, the other on the shoulder of a little boy. The old man gazed into the distance, beyond the frame, while the little boy stared happily up at the man who seemed to be the boy’s grandfather. Behind them, old wooden houses appeared, nestled close to each other, an unpaved road in front of them. Drawn with the thin lines of a needle and outlined in black ink, without color or paint, the lithograph portrayed an entire world that breathed with life.

Collecting antiques and old Judaica was my friend’s hobby, and he tried to entertain me with stories of recent acquisitions from auctions, markets and, at times, brazenly haggled directly from his friends’ walls. Yet the only work that piqued my interest was that simple lithograph. “Who drew this?” I asked him. “Kaplan. He spent most of his life in Leningrad but was born in a village called Rogachov.” “Rogachov?” I repeated with astonishment. “Rogachov?!”

Though for many the name of this shtetl in what is now Belarus may mean very little, I had been hearing its name since I was a small child. My grandfather was born in Rogachov. This is where the oft-repeated stories of his childhood, his escapades in cheder, his memories of his parents and friends all came from. This is where, in the early 1940s, his parents and sister were murdered by the Nazis in the Rogachov Ghetto. “Yes, this must be Rogachov!” – though I had never seen Kaplan’s works before, his depiction of this shtetl was exactly the way that I had always pictured the little town where my family came from.

credit

My earliest recollections of Rogachov take me back to my grandfather’s apartment in the center of Leningrad in the mid-1970s. Brezhnev’s gravelly voice comes booming from the old wooden radio and my grandfather’s reaction makes me laugh as he mimics, with perfect timing, the aging Soviet ruler’s accent, the way in which Brezhnev smacks his lips, his ubiquitous self-praise, his stumbling over words. As we listen, my grandfather stops every few minutes, his eyebrows raised exactly like Brezhnev’s, to copy his mock surprise at the deafening applause by the sweaty hands of countless sycophants in the large Kremlin Hall where the speeches are delivered.

As Brezhnev fumbles on, my grandfather slides open the bottom drawer of a small wooden night table next to his couch-bed, where an old tattered photograph of a writer I will later learn is Isaac Babel – and to whom I will dedicate many years of study – rests in between yellowing issues of Pravda. On top, a well-worn brown covered volume, one of six – the others were kept behind sliding glass drawers in bookcases next to his writing table – lie waiting. As he leans back on his rickety chair, my grandfather flips through well-thumbed pages, stopping as he reaches the page he is looking for. I listen and laugh as he reads the stories of Sholem Aleichem in his Yiddish-accented Russian.

These stories would inevitably lead my grandfather to become whimsical and he would regale me with memories of his youth. “Rogachov was Kasrilevka,” he would say, intoning the name of Sholem Aleichem’s made-up town that serves as a prototype of a Jewish shtetl and the location of the escapades of the simple “little Jews.” He would then recall his Rogachov, the people, his siblings, aunts, uncles, weddings, funerals, the wooden homes, the streets, his cheder and the way he and his friends would play games and mock their teachers.

He would tell me of Rogachov’s “main store” that had just two shelves: on the first, dry pasta and sugar, on the second, a few pairs of galoshes. “So what did people eat?” I would ask. Everyone had chickens, grew vegetables and fruit in their small gardens, the wealthier would have a goat that provided milk, the really rich had a cow. His brother, Michael, a doctor, still lived there then and my grandfather would visit him at least once a year. “When we arrive at the station,” he would tell me, “we have to jump off the train quickly as the stop in Rogachov lasts for one minute only.” And he would describe how they milk the cows and collect eggs from under the cackling hens every morning.

“As a kid, I would always wear the same cap, even when it got small. I had one pair of pants, a pair of shoes, and two shirts. In the winter, my brothers and I would share a warm coat. But we never felt like we were lacking. We had everything.” And he would sigh, sip from his glass of hot tea, and return to Sholem Aleichem.

** ** **

The Life of an Enchanted Artist

Childhood and Youth

Tanchum Kaplun (Anatoly Kaplan) was born to Levi Yitzchak and Sarah on December 28, 1902 in the town of Rogachov, a small shtetl in the Gomel region, on the banks of the Dnieper River. He had five siblings and was the third child, known for his quiet disposition and prone to wandering off into the forest. Tanchum’s father and grandfather were kosher butchers; his father owned a small meat stall in Rogachov that he had inherited from his father. The family were Kohanim, from the ancient priestly lineage (which would later inspire Kaplan to create ceramics with the image of the blessing of the Kohanim). At the age of six Tanchum entered cheder; two years later, his parents sent him to a state school where he studied in Russian.

In his youth, Kaplan would paint signs for local shopkeepers together with his friend Samuil Galkin (also known as Shmuel Halkin). Galkin, who was born in Rogachov in 1897, would go on to become a well-known poet in the Soviet Union.

On frequent visits to his brother, who lived in Kharkiv, Kaplan saw his first art exhibitions. While there, and already showing artistic talent, Kaplan entered a training program for teachers and in 1919 received a diploma that allowed him to teach painting in state schools.

Early Years as an Artist

The young and aspiring artist yearned to continue his art studies. In 1922, Anatoly Kaplan moved to Petrograd and entered the Petrograd Academy of Arts where he studied until 1927.

Boris Suris, a prominent Soviet art critic, described the somewhat volatile situation at the Academy in the early years after the Russian Revolution:

“The Academy was undergoing turbulent changes. There was a complex process of reassessment of values; the old system of art education was mercilessly breaking down, while the new one was just beginning to take shape through difficult, often contradictory and not always fruitful searches and experiments. Among the leaders of the workshops there were representatives of almost all the then existing, warring groups and trends – from the heirs of the old academic traditions… to the extreme leftists. Students had to obey guidelines, sometimes diametrically opposed to each other… Kaplan also had to live through all this discord.”

Despite the difficulties of these changing times, Kaplan’s education benefited from classes by outstanding artists such as Arkady Rylov, Nikolai Radlov, and Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin.

While at the Academy, Kaplan shared a room with Dov-Ber (Doyvber) Levin, a Yiddish writer who is now mostly forgotten. Unlike Kaplan, who is not known to have joined any new ideological or artistic movements, Levin was a member and one of the ideologists of the OBERIU (Union of Real Art) literary group founded by Daniil Kharms.

In 1928 Kaplan designed the set for Kharms’ play Elizaveta Bam. Though his set designs were accepted, Kaplan terminated the collaboration, apparently concerned that his Academy professor, Arkady Rylov, would disapprove of his involvement. Though he would later speak about the influence of Daniil Kharms and the OBERIU group on his work, at the time the young man from Rogachov was being careful.

credit

Despite these concerns, Kaplan’s friendship with the Oberiuts continued. When Levin started writing stories for children, he commissioned Kaplan to illustrate two of his books about the life of Jewish shtetls in the pre-Revolutionary years and the years of the Civil War. Both published in 1932, the Street of Shoemakers describes the path of a Jewish teenager to the Revolution, and The Free States of Slavichi is about a 33-hour period in power of an anarchist gang in a Jewish shtetl. This was the start of Kaplan’s career as a book graphic artist. His illustrations drew on themes he would later repeat in his lithographs, paintings, etchings and ceramics: horse-drawn carriages, wooden houses, rooms with clocks on the walls, wooden beds, furnishings, framed pictures of older relatives, scenes from the villagers’ everyday life, modern looking men as well as bearded, cap-wearing old Jews who represented the old generation, scenes on riverbanks, children with goats and youth in rowing boats.

That same year, Kaplan illustrated a children’s book by Alexander Razumovsky, also a member of the OBERIU. Called Soviet Revolutionary Committee in the Desert, the book is a story for children about the Soviet rule in Turkmenistan. Kaplan’s approach to his illustrations closely followed the artistic style that he used for his work for Levin, though his attention to detail and the play with light and shadow helped create the atmosphere of Central Asia. One illustration, however, On the Train, depicting a snoring, bearded passenger being awakened by the overly loud voices of two young fellow passengers, looks very much like an unhappy Tevye and bearded Jewish men that would later appear in other Kaplan drawings.

Over the next decade, Kaplan frequently returned to his hometown. He drew Rogachov’s winding unpaved roads, narrow alleyways and wooden houses. He sketched and drew animals, especially his beloved goats, and the people of Rogachov: his parents, sister, friends, wagon drivers, blacksmiths, cobblers, beggars, peddlers, as well as self-portraits as a young man.

When relatives or friends from Rogachov visited Leningrad, Kaplan’s mother would send her son care packages. In 1934, Yevgeniya (Gina) Libman, a young woman from Orgeev , delivered a package of homemade food from Kaplan’s family. By that time, Kaplan lived in a communal apartment on Dumskaya Street, in the very center of Leningrad, with no toilet and water available from one shared tap at the end of the corridor. None of this seemed to bother Gina, who was taken with the book illustrator. They were married the same year. In 1935, their daughter and only child Lyuba was born. She was a sickly child, with acute special needs. Kaplan tried to teach her to draw and she was taught to eat by herself but otherwise had to be taken care of for the rest of her life. Kaplan’s sister, Dasya, lived near him in Leningrad and would often visit her brother and take care of his daughter.

The 1930s, Stalinist Terror and Kaplan’s First Lithographs

The 1930s was a period of brutal oppression and persecution. Known as the Great Purge, Stalin’s henchmen began to remove the Old Bolsheviks and others perceived to challenge Stalin’s authority, including writers, intellectuals, artists, and religious activists. Torture, violent interrogations, and arbitrary executions caused more than a million deaths that included thousands of Jewish cultural and political leaders.

Alongside the hellishness of the purges, the early 1930s was also witness to the heavy-handed implementation of Socialist realism, with its attempt to relegate all works of art to the service and promotion of Soviet ideals. Adherence to party doctrine was ruthlessly enforced to ensure that all toed the party line in the production and presentation of art, film, theater, literature, and architecture.

Paradoxically, in the very years of the Great Terror, Leningrad’s State Museum of Ethnography of the Peoples of the USSR began to work on an exhibition called Jews in Tsarist Russia and the USSR. Led by Jewish ethnographer Isai Pul’ner, the focus of the exhibit was to popularize the idea of resettlement to the Jewish Autonomous Region. Under pressure to present the glory of the Soviet Union’s accomplishments but with no items to display, Pul’ner turned to Anatoly Kaplan, known in the city as an artist who depicted scenes of Jewish life.

For the exhibition, Kaplan was commissioned to create lithographs, an artistic technique that he had no experience with but one that interested him immensely. Over the next two years, he studied lithography at the Experimental Lithography Workshop of the Leningrad Union of Soviet Artists, a new section organized as yet another way of bringing realist socialist art to the Soviet people.

At the Workshop, Kaplan studied innovative techniques with masters of lithography. These included Nikolay Tyrsa (a student of Léon Bakst), Vladimir Konashevich, Konstantin Rudakov, and the celebrated graphic artist Georgy Vereisky. Due to the perception that lithography would not be too popular among the masses, the Experimental Workshop was under far less ideological scrutiny, providing its teachers and students with a greater level of creative and artistic freedom away from the prying eyes of government censors.

In 1957, Kaplan would recall his days studying with Vereisky: “Georgy Semenovich would bring us lithographs by outstanding Russian and French artists from his own collection. He showed us works of Serov, Daumier, Gavarni, explained them, revealing to us how these masters achieved expressiveness and beauty in their works. Georgy Semenovich gave us a great love for the work of lithography; it is thanks to him that I learned this technique.”

Learning from Vereisky, Kaplan mastered the tools that enabled him to create different perspectives, angles, manipulate light and shade, adding silver and gold for a rapturous effect. These unique artistic techniques enabled Kaplan to breathe life into the characters he portrayed while also creating landscapes of multi-layered narratives.

From 1937 to 1940 – as the flames of the Great Purge burned and people disappeared into the clutches of Stalin’s murderous lackeys – Kaplan produced his first series of lithographs, Kasrilevka, which showcased his talent for portraying the past as if it was not gone, as if it all still existed. Kaplan’s artwork recreated the Jewish world he came from in an emotional, imaginative, humorous and realistic manner, combining folk art traditions with the technique that expressed a great depth of feeling.

Vladimir Konashevich, a friend of Kaplan’s and himself a graphic artist, vividly recalled the way Kaplan approached his work at the lithography studio: “The first time I saw him, [Kaplan] was bent over the stone, which he rubbed, scraped, smeared with ink, and inked again, scratching and rubbing with all the tools he could get. This was an adamant, persistent battle: he attacked the stone, trying to break the resistance of the stubborn material at all costs. I was interested in this fight: I wanted to see what this ‘tormentor of stone’ would achieve. And what did his efforts produce? The very first drafts of his works showed that he had broken through the stubbornness of the material.”

By 1939, the young man from Rogachov became a member of the Union of Soviet Artists, this being the first step on his way to becoming a recognized Soviet artist allowed to participate in government sanctioned exhibitions.

The Siege of Leningrad

As the German forces surrounded Leningrad in 1941, Kaplan stayed in the city during the most fierce and horrendous period of the first year of the blockade. One can only imagine the tragedies that he witnessed in the city under siege, with daily bombardment, grisly fear, extreme starvation, and death. Despite this, he continued to work and later was awarded a medal for his acts of bravery.

With the situation in Leningrad worsening, in the spring of 1942 Kaplan was evacuated, together with his wife and eight-year-old daughter, to Chusovoy in the Ural Mountains. His lithography work was interrupted but he was able to create many pencil drawings, watercolors, and works in charcoal, mostly of local scenes and people he observed. In 1942 and 1943, Kaplan participated in art exhibitions in Perm and Sverdlovsk respectively.

The siege of Leningrad continued until January 27, 1944, but Kaplan was only able to return to the freed city in April of that year. Leningrad was beginning to slowly recover from the 872-day blockade. Kaplan returned alone, without his family. There was little work and he took on any assignments he could get, writing slogans, street signs and posters while living in a small communal apartment in the center of Leningrad.

The Rogachov Ghetto

Throughout the war, Kaplan persistently worried about his parents and siblings who still lived in Rogachov. Due to Soviet suppression of information about the horrors of the Holocaust and the personal difficulty of facing such tragedy, Anatoly Kaplan was never able to write about the fate of his beloved shtetl during the war. I do it here now for him and for the many others who couldn’t.

The Wehrmacht occupied Rogachov on July 2, 1941.

In September 1941, three ghettos were created in different parts of the city, separating men and women: the first for the able-bodied, the second for the disabled, and the third for teenagers. In total, more than 4,000 Jewish people from Rogachov and the surrounding towns were driven to these ghettos.

The ghettos were guarded by Nazis and local policemen; anyone caught leaving was shot on the spot. Famine began after the first few days, followed by disease. The only food available was that received from the guards in exchange for valuables or stolen from agricultural work. Local non-Jews were forbidden to help Jews under threat of death. Life inside the ghetto was horrific: Jews were used for forced hard labor, with many dying from unbearable exhaustion, constant hunger, torture, and lack of medical care.

Between the months of October and March of 1941, more than 4,000 Jews were taken from the ghettos and murdered. Some were taken to a ditch about 70 meters from the Drut River where they were forced to undress and then were shot with machine guns or rifles. Others were taken to the cemetery on Frunze street, a place that after the war would be called The Valley of Death. Babies and little children were killed by throwing them on the frozen ground. In the spring of 1942, during a flood, many bodies from a mass grave floated up to the surface. The Germans ordered the inhabitants of Rogachov to fish out the remains from the river and bury them again on the bank. Before their retreat in December of 1943, the Germans dug up the bodies and burned them for three days to try to hide the traces of their crimes.

Rogachov was recaptured by the Soviet army on February 24, 1944.

The Jews who were murdered included Anatoly Kaplan’s family – and my great-grandparents, their children, and other members of our family. Kaplan’s sister, Dasya, was the only one in his family to survive.

All of this Kaplan would learn on his post-war visit to Rogachov.

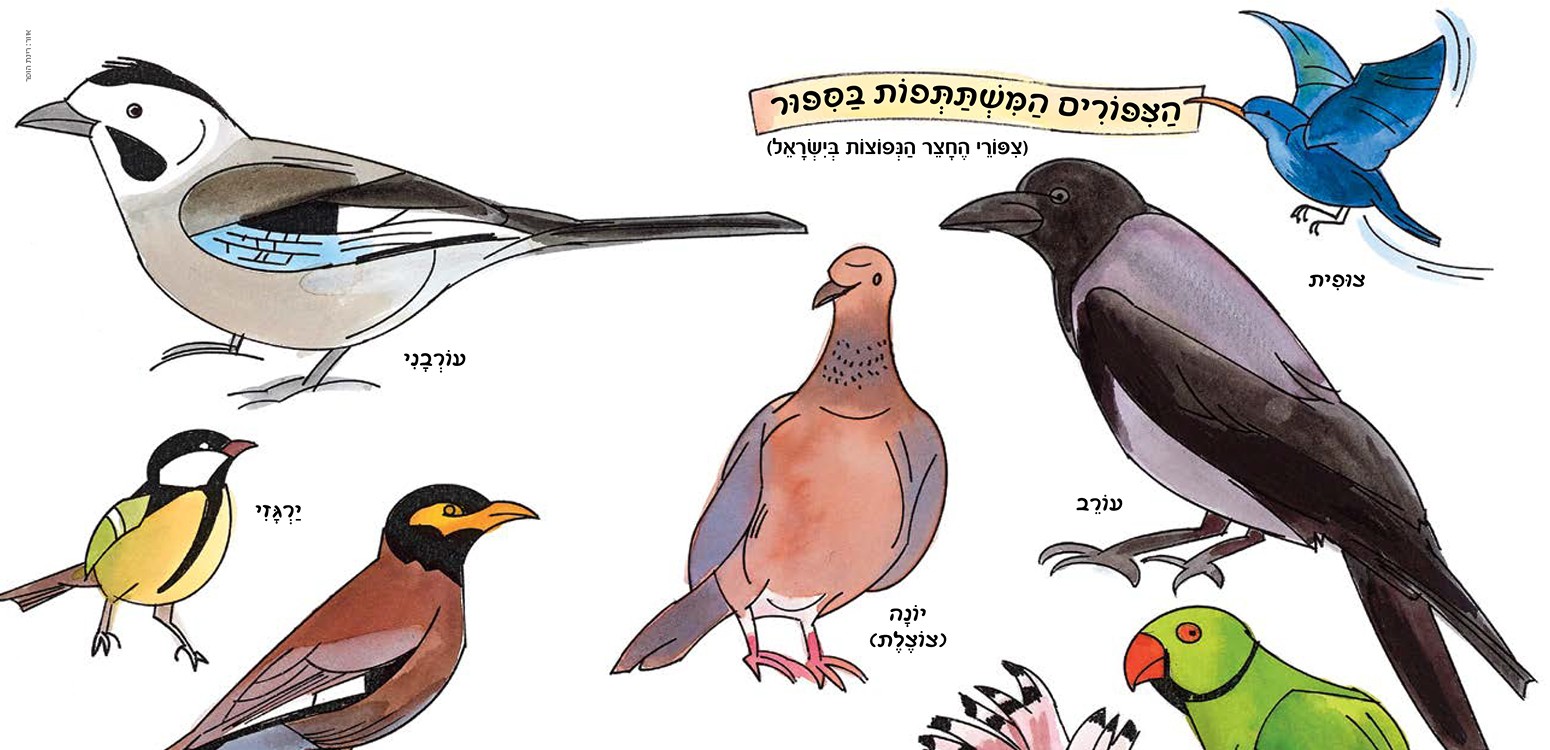

Despite the horrors, his 1951 works titled Rogachov: Morning and Rogachov: Sunny Day are poignant depictions of the town as he remembered it before the travesties of the war. Wooden houses, tall trees, people walking together, white goats and animals caught in the rain. Yet he also draws small birds that appear above branches of trees flying through a cloudy sky. Perhaps they represent ethereal memorials to all those whom Kaplan lost.

Kaplan in Leningrad Following WW II

After returning to Leningrad, Kaplan threw himself into painting the recovering city he saw around him. Once again using lithography as his artistic medium, Kaplan aimed to capture the healing city as it returned to life.

He printed the first works in his Leningrad series in 1944, the second part of the series, called Recovering Leningrad, in 1945 and 1946, and the third, Leningrad Landscapes, in 1947 to 1949.

The images of Leningrad breathe with memories of the past, expressing pain, darkness, emotion and yet, through play with dark shadow and streams of bright light, with courage and promise. As so often, Kaplan’s works create the feeling that one is reading a poetic masterpiece filled with aspects of darkness but at the same time radiating with discernible hope.

Describing the Leningrad series, Natalya Kozyreva, head of the Department of Drawing and Watercolor at the State Russian Museum, writes: “Kaplan’s Leningrad series is one of the most striking and poignant declarations of love known to world culture. The works are at the same time expressions of love-farewell and love-remembrance, love-hope and love-repentance.”

When the series was published in 1946 as Leningrad During the Siege, it was purchased by 18 museums in the Soviet Union and provided Kaplan with significant exposure as an artist.

Escaping the Great Terror

The post-World War II years renewed the horrors inside the Soviet Union. The gradual liquidation of Jewish cultural institutions that began with Stalin’s ascent to power continued, with art being further devastated and repressed. During these years, many Jewish academics, journalists, those who had served in the army, and other professionals were dismissed, arrested, or disappeared. The murder of famous Yiddish actor Solomon Mikhoels in January of 1948 and the subsequent closing of the Moscow State Yiddish Theater (GOSET) in November of 1949 were followed by the mass arrests and murders of Yiddish writers in August of 1952; Yiddish book publishing ceased completely until 1959.

It was no longer only Jewish religious life that the Soviets wanted to eliminate – they now also sought to crush all remnants of Jewish secular culture. The Soviet Union’s initial support of the creation of the State of Israel quickly turned to overt antagonism, with the Hebrew language and any correspondence with relatives or friends in the West viewed as treason.

By all accounts, it seems that Anatoly Kaplan was able to successfully avoid the pressures of Socialist Realism and Soviet ideological critics by aligning himself with and working for art institutions that enabled him to pursue his creativity. His decision to illustrate children’s books early on in his career shielded him from the authorities as children’s literature in the Soviet Union, at least in those days, was far less regulated; the Leningrad Experimental Lithographic Workshop where he learned the techniques of lithography also provided cover from Soviet censors.

In 1950-1951, Kaplan secured work as chief artist of the Leningrad Glass Art Factory. In his short time there, decorative and household items were made according to his designs; his techniques improved stained glass production. Though he thought that this position would shield him from Stalin’s antisemitic purges, he was fired in the early 1950s. During the years that followed, Kaplan turned to illustrating works by Anton Chekhov and Vladimir Korolenko.

A Match Made in Heaven: Anatoly Kaplan and Sholem Aleichem

The Soviet Union breathed a sigh of relief with Stalin’s death in March of 1953. Over the period commonly known as the Thaw, under Nikita Khrushchev, repressions and censorship were relaxed. This may have given Kaplan the confidence to embark on the project that was to be his focus in the years to come: creating works of art for stories by Yiddish writers, primarily those by Sholem Aleichem.

Kaplan was over 50 years old when he began drawing for the stories of Sholem Aleichem. Yet when the artist placed himself alongside the writer in his lithographs, Kaplan drew himself as a man in his twenties. The world that Sholem Aleichem wrote about is the world that Kaplan had always been in love with. Kaplan knew this world from up close, from inside. Kaplan had absorbed the traditions and life of Rogachov, and despite all his years in Leningrad, he never forgot what he saw and felt as a child.

In 1888, with a voice of prescience, Sholem Aleichem penned words that could perfectly describe the relationship between him and Kaplan:

“A writer, a folk writer, an artist, a poet, a real poet for their time, is a kind of lamp in which the rays of light are reflected as in a pure source…the rays of the bright sun …There is a strong, eternal connection between the people and the writer; therefore each writer is for his people both a servant and a priest, a prophet, a champion of truth and justice; therefore, every nation loves such a servant of God…a fighter who consoles the people in their grief, rejoices in their joy, and expresses their ideas, thoughts, hopes and expectations.”

Theirs was a match made in heaven.

As he began to draw Jewishly-themed images in the Leningrad of the early-1950s, Kaplan was nevertheless concerned about the reactions of his neighbors. He lived in a communal apartment and, while drawing, attached the drawing paper to the back of his door so that if the neighbors looked in, they would not be able to see the content of his drawings.

The Enchanted Tailor and Tevye the Dairyman

Kaplan’s lithographs for The Enchanted Tailor, which he began working on sometime in the early 1950s, are created with the use of a frame: along the rim of a large sheet Kaplan drew either ornamental patterns or little scenes with goats, cows, horses, and birds, often with Yiddish or Hebrew text that borders the main image, in which “the viewer sees the hero of the legend, an enchanted character being transported into the realm of a sad, but magnificent fairytale.” Kaplan worked on this series for more than five years. Outside his window, Soviet Leningrad awoke and went to sleep; yet inside his room, on his large canvas, Kaplan spent days and nights recreating the world of the past that he wanted to protect forever.

From 1957, Kaplan begins working on the Tevye series. He chooses to create these works in monochrome, as he had previously for his Kasrilevka series, without decorative frames or color. Eventually numbering more than 100 separate lithographs, Kaplan’s Tevye breathes with emotional graphic expressiveness and includes portraits, domestic scenes, landscapes, and detailed depictions of entire villages that art critics have even compared to the likes of Bruegel.

“These two works became for Kaplan not material in need of illustration so much as a kind of real world that had its own time and space and in which the succession of events was not the most important aspect,” writes Mikhail German, leading researcher of the State Russian Museum. “Kaplan became an artist – perhaps the only artist of his time – who depicted the reality presented in books as another, artificial world… like illustrative memoirs whimsically mixed together with a stream of literary associations.”

When looking at Kaplan’s depictions, it seems as if Sholem Aleichem wrote his stories based on Kaplan’s drawings, and not the other way round. Having seen the lithographs once, the scenes and characters from Sholem Aleichem’s stories forever stay with the reader in the form that Kaplan created for them.

Chad Gadya and Jewish Folk Songs

From 1957 to 1963, Kaplan drew artworks for his Chad Gadya series (1957-1961) and for Jewish Folk Songs (1958-1963). He created his Jewish Folk Songs in two versions, one in tempera and the second in color, basing them on the Russian folk tradition of wood engravings called lubok. In these works, Kaplan tried to follow the Soviet idea of a happy life for the Jews: “nationalist in form and socialist in nature.” One notices some deviations from the happy depictions, but these works are mostly drawn without any sense of the hardships suffered by Jews.

Chad Gadya Without God

The image of a white goat is one that Kaplan, like Chagall before him, returned to repeatedly in his art. The white goat appears in Kaplan’s drawings of Rogachov, in many of his later illustrations, and on the cover of the album he created for Chad Gadya.

Taken from the Passover Haggadah, Chad Gadya is a strange and haunting song that addresses the topics of vengeance and retaliation. Though seemingly simple, there exist numerous interpretations of the song, relating the narrative to the history of the Jewish people.

Unlike other Jewish-Russian artists who drew the series with quite frightening imagery, Kaplan’s draws in bright color and happy tones. What sets Kaplan’s Chad Gadya artworks apart from the others is the text he chose to illustrate – and that which he chose to ignore or change.

After following the traditional lines of the song, Kaplan surprisingly stops his artworks at the line “Then along came the ox and drank the water.” He then skips the next two parts, the one that refers to the shochet (Jewish butcher) who slaughters the ox, as well as the line about the angel of death killing the shochet. And he changes the final stanza of the song from “Then came God and killed the angel of death…” to “A man came and harnessed the ox.”

In the 1981 German edition of Kaplan’s Chad Gadya, the editor explains that the reason that Kaplan rewrote the final line was to do away with God and to emphasize “a working man’s quest for peace.” Perhaps under the watchful eye of a Communist censor, the East German editor writes: “Kaplan’s artwork shows a chain reaction of violence, but also the overcoming of violence by the working man who strives for harmony.”

Yet the explanation for Kaplan’s version may be quite different. Kaplan was the son and grandson of Jewish butchers; his family was murdered by the Nazis. He did not want to depict Jewish butchers as murderers – or those being murdered. There was sufficient murder in his time as it was.

As for the last stanza, the one that excludes God and instead speaks of man, it can far more readily be explained by the complicated conditions in which Kaplan lived. In fact, in his 1961 preface to Kaplan’s collection of Tevye lithographs, Ilya Ehrenburg does not even mention the word “Jew” to ensure that his introduction would not be rejected by censors. In this context, Kaplan’s choice to not include any reference to God in his version of Chad Gadya becomes understandable.

Finally, in his artworks for Chad Gadya, Kaplan uses Hebrew letters and drawings of goats, lions, birds, and other animals, replicating images often found on tombstones in Jewish cemeteries. These images were often used to symbolize life beyond death. In the Aesopian language that he was forced to use, Kaplan includes the Divine in his Chad Gadya after all.

Song of Songs and From Jewish Folk Poetry

In 1962, Kaplan creates artwork for Sholem Aleichem’s Song of Songs. Published in 1910, the short novel describes the innocent love between a young man and woman who have known and loved each other since childhood but separate because of another young man. Pining for the world of childhood, Sholem Aleichem writes this tragic and beautiful tale by interspersing expressions of endearment in Yiddish, the everyday language that somehow cannot sufficiently express the language of love, with the holier language of the Biblical Hebrew in the Song of Songs.

As he did with his artwork for The Enchanted Tailor, for Song of Songs Kaplan again draws images within images, with the love between the two main characters depicted in the center, surrounded by a series of smaller, stamp-like scenes drawn in frames around the page. Kaplan’s artistic interpretation powerfully evokes the emotion of the story, with the image of a small goat serving as a silent witness.

From 1962 to 1963, Kaplan creates artwork for Russian composer’s Dmitri Shostakovich’s late 1940s song cycle From Jewish Folk Poetry. Kaplan creates this series using gouache and tempera, basing the color scheme on the theme of each particular song. In some cases, he uses full, bright color, in others – more subdued or black and white tones, with each work decorated with the Yiddish text of the song, at times translated into Russian. As we view the individual works, we can hear the music of Shostakovich rising and falling.

Stempenyu

From 1963 to 1967, Kaplan creates artwork for Sholem Aleichem’s Stempenyu. Written in 1888, this was Sholem Aleichem’s first Jewish novel that offers rich detailed depictions of the Klezmer world, touches on the important cultural role that Klezmer musicians played, and also shows the town life within the Pale of Settlement.

Kaplan created more than 100 separate illustrations for Stempenyu, playing with shade to create swirling, dancing, romantic images. These illustrations imbue shtetl life and people with poetic beauty and sparkling energy.

When one stands back a few paces from the lithographs, one can almost hear the Klezmer musicians play, see the characters moving, feel the energy that imperceptibly and surrealistically transforms us into guests inside Kaplan’s world.

Stories for Children

From 1965 to 1970, Kaplan works on illustrating Sholem Aleichem’s Stories for Children. For this series, Kaplan chooses to use large sheets of paper divided into separate frames. Each frame displays a different scene from the story, with the portrait of the main character in the center. Using this approach, Kaplan is able to retell the entire story on one sheet. In addition to the 26 main lithographic sheets for Stories for Children, Kaplan created a small mini-series: four sheets in color and nine sheets in black and white for The Penknife, and nine black and white sheets for The Clock. Kaplan also created four works in pencil to illustrate Methuselah (A Jewish Horse).

Fishke the Lame

Kaplan’s deep feelings of mourning for the world that is no more are particularly seen in these works that he created from 1966 to 1969 for this bittersweet story about a crippled beggar named Fishke, his love for a hunchbacked girl named Beylke, and the life of the shtetl’s cripples and thieves. The artworks immediately calls to mind the cemeteries of East Europe and the stone matzevot with engravings of scenes from the life of the departed. The visual effects Kaplan is able to achieve are quite astounding; the illustrations seem to be etched in stone, immediately setting the mood and providing a masterfully precise artistic interpretation.

Stories for Children were to be Kaplan’s last Sholem Aleichem project, and together with his artwork for Mendele Moykher-Sforim’s (Sholem Yankel Abramovich’s) Fishke the Lame, his final use of lithography. Kaplan was over 60 years old when he created these illustrations. Nevertheless, in his works he once again returns to his childhood home of Rogachov and mourns all that was lost.

Ceramics

Encouraged by Isaak Kopelyan, a Leningrad artist and editor of many of Kaplan’s lithographic works, in 1967 Kaplan begins to explore the world of ceramics.

Mastering the technique independently, Kaplan sculpts from fireclay, molding, painting, glazing, at times adding forms onto flat slabs of clay, using engobe to decorate and to give his ceramics depth, color, dimensions, and visual range. As with his approach to lithography, Kaplan becomes a tormentor of clay, pinching, digging with his fingers, using metal objects to form shapes, at times adding gold, glaze, shiny glass, at others using simple lines and forms to create powerfully expressive and emotional pieces.

The subjects for Kaplan’s ceramics are variations on his favorite themes: Jewish ritual items, domestic Jewish scenes, a mother lighting candles, dancers at weddings, klezmer musicians, children at cheder, teachers studying Torah, lovers, framed portraits of people whom he remembers. Turning to painting on large ceramic plates, Kaplan creates new versions of his Chad Gadya series as well as Jewish ritual objects, dancers, songs, lovers, goats and other animals and scenes from his beloved town. The plates are often framed by Yiddish verses and lettering and filled with bright color, expressing tenderness, movement and a sense of angelic harmony.

There are several especially moving ceramic pieces, some that Kaplan creates as sculptures, others as flat slabs that remind us of matzevot, that he dedicates to the memory of his family. One depicts his parents in their younger years, their names inscribed in Hebrew letters, an image of a lion above his father’s face, an image of a bird above his mother’s.

In the 1970s, Kaplan creates 38 sculptural portraits for Nikolai Gogol’s Dead Souls and 25 for Inspector General. In a 1979 article that appeared in Germany, a year before the publication of Dead Souls with 37 Sculptures by Anatoli Kaplan, Kaplan is quoted as saying, “After I reread Dead Souls, I could visualize each character, their faces and their psychological makeup so vividly that I had a strong desire to give them form. Soon, I was so possessed by this work of creating that I began producing a whole series of characters. So I carved 38 busts for Dead Souls and 25 busts for The Inspector.” Additional reasons motivating Kaplan to undertake this work may have been Sholem Aleichem’s admiration for Gogol and Marc Chagall’s 1920s drypoint illustrations for Dead Souls.

For his Gogol series, Kaplan does not use glaze or color, creating the sculptures in unpainted fire clay with uneven surfaces. This approach allows the characters’ facial expressions to change depending on the way in which they are illuminated or are in shadow. Donated to the Russian Museum, Kaplan’s Gogol sculptures evoked much admiration. In this period, Kaplan also creates busts for Isaac Babel’s Odessa Stories.

Pastel

In 1971, Kaplan begins to create artwork in another new artistic medium – by working in pastel. In total, Kaplan creates 400 pastel paintings in the last decade of his life, each sheet filled with the memories of his youth or one of his favorite subjects.

Etchings and Drypoint

In the 1970s, Kaplan works in charcoal and slate pencil and repeatedly returns to his Jewish childhood memories of Rogachov. He also masters yet another art form: etchings and drypoint. In 1976, Kaplan works on a second series for Fishke the Lame and, in 1977, a second version for the From Jewish Songs series, with both series created in drypoint. Once again, Hebrew letters with the names of the characters whom Kaplan chooses to portray surround each scene.

Through the Stroke of a Brush: Kaplan the Master Storyteller

In 1961, Ilya Ehrenburg, an influential Soviet writer and journalist, would compare Kaplan’s work to that of Chagall and Soutine. “They all shared,” Ehrenburg would write, “not only the memories of wooden houses, shop signs, bearded old men and dreamy young people, but also a sense of existing in a fairy tale, of tragedy and, at the same time, a passionate love of life. All this is expressed not in literal retelling, but in the language of art.”

Influential art critic Boris Suris spoke more candidly about the difference between the famed artists: “In Kaplan’s work, there is neither Chagall’s stunning unbelievability, nor Soutine’s hysterical, suffering brokenness.” He calls Kaplan “a realist” and “a lyricist to the marrow of his bones, his element – a penetrating poetic feeling that is poured into all of his works. Chagall is also a lyricist, and one cannot deny him the ability of being amazingly truthful. But [Chagall’s] lyrical excitement is excruciatingly overstrained, his overexcited imagination hallucinating.”

Anatoly Kaplan’s work presents the world as it is. “You will find in his works no abstract, hypertrophied image or concepts of Death, Birth, Suffering, Dream of the kind that you often find in Chagall,” writes Mikhail German. “His drawings and pictures contain no direct symbolism. Instead, Kaplan’s symbolism is concealed behind accurate, precise demonstrations of detail… the impressive quality of [Kaplan’s] drawings lie in the fact that in them nothing is concealed or encoded. They are clear, utterly devoid of ambiguity. And, like a kind of emotional axiom, each line is so precise that it takes one’s breath away with its perfect, utter expressiveness.”

In Kaplan’s art, one does not see floating or dancing characters, his mystery is what lies inside the rickety wooden homes, behind the eyes of the people he depicts, in the emotions that he portrays when he juxtaposes the young and the old. “Kaplan is in his own way no less metaphoric than Chagall, but his metaphors do not escape, so to speak, onto the surface of the image… the major world problems, the ‘eternal questions’ that Chagall was so fond of returning to remain locked in the image’s innermost depths.”

“[Kaplan] views the houses of his native city… with undisguised admiration. In his eyes, the structure of logs and planks, the rhythm of the old windows and steps conceals an infinite number of magical mysteries… you could say that… the poetry of his drawings is exclusively a matter of their piercing, stunning resemblance to reality – that special, unquestionable resemblance to reality that can be understood without comparing the drawing to the original… He sees and draws the houses through the prism of his miraculously surviving childhood impressions, through the mist of his memories, accentuating every little crack and every crooked twist of the roof with the everlasting sorrow felt for the passing joy of the first impression.”

Outside the Soviet Union

During a trip to Moscow in December 1957, Kaplan befriended writer Samuil Marshak and writer and journalist Ilya Ehrenburg. Kaplan gifted both men a number of his works and appealed to Ehrenburg to use his connections in the West to arrange exhibitions of Kaplan’s work.

Through the help of the East German consulate in Leningrad, German artists and journalists came to see Kaplan’s artwork. Reviews were published in German magazines, and commissions started pouring in, including illustrations for Sholem Aleichem’s stories in German translation. Partly due to their appreciation of his work, partly given Germany’s desire for atonement, 25 albums of Kaplan’s works were published in East Germany, with the works favorably reviewed in the German press.

When the East German Minister of Culture visited Kaplan in his home (Kaplan was not well and could not attend the official meeting at the Leningrad Union of Artists), he was horrified by the conditions of the communal apartment that Kaplan lived in. Following the visit, the Soviet government, embarrassed by the German minister’s impressions, finally granted Kaplan a small private apartment.

Rudolf Mayer, a German publisher who headed Verlag der Kunst in Dresden, was an admirer, collector and publisher of Kaplan’s works and would visit Kaplan often. In 1960, Mayer introduced Kaplan to Eric Estorick, an American-born art dealer and philanthropist of Jewish origin who owned the London-based Grosvenor Gallery. This meeting proved critical in introducing Kaplan’s artwork to audiences outside the Soviet Union.

Though Estorick bought works by 27 Leningrad artists, it was the art of Kaplan that he was taken with the most, purchasing 90 lithographs. In 1961, two exhibitions took place at the Grosvenor Gallery in London: the first of all 27 Leningrad artists and the second exclusively of works by Kaplan. This was Kaplan’s first solo exhibition and his first venture outside the Soviet Union (though he himself was never allowed to travel abroad).

Estorick’s exhibition generated sales to museums in the UK, Germany, France, Italy and the United States as well as to private collectors and garnered highly favorable reviews in the media. The Daily Telegraph art critic wrote: “Kaplan is one among only two or three contemporary artists about whom I am certain posterity will have no doubt”, while the Burlington Art Magazine compared Kaplan’s art to that of Marc Chagall. In 1961, Estorick organized an exhibition of Kaplan’s artworks in New York and, in 1962, at the Bezalel Museum in Jerusalem.

In 1972, Estorick also commissioned an impressive Russian hard-cover color album of Kaplan’s works with an introduction by art critic Boris Suris. The book was prepared for publication but having faced constant delays in Russia, it was finally published in Leipzig.

When Kaplan received the album, he was surprised to see that the censors had removed the Star of David from his illustration for Weeping over a Dead Child in the From Jewish Folk Poetry series. A few years later, Kaplan purposely removed a Star of David from his Mother of Death etching (the Rogachov series) since he felt that the Russian Museum that was interested in acquiring the work may reject the entire series if a Star of David made an appearance. These are the struggles that Kaplan had to endure.

For 12 years, Kaplan was the most profitable Leningrad artist. However, the Soviet government policy meant that the income from sales of art went to the State, with Kaplan receiving only about 2% of the profit from his own artwork.

Last Years

The last years of Kaplan’s life were not easy. He was often not well and had to take breaks from work. Yet almost until his last days he was working on his Rogachov series. Here, Kaplan once again returns to his childhood but no longer calls the series Kasrilevka as he had done in his younger days. He confronts his personal memories directly, without hiding behind acclaimed Jewish authors or succumbing to the fear of depicting unambiguously Jewish themes.

In Mourning (1975) Kaplan shows the death of a child, his mother crying, his father looking up with sorrow as a memorial lamp is lit nearby. In Grief (1976) his needle creates a scene of a Jewish burial, the deceased being carried to the cemetery. Before the burial procession, mourners appear, one holding a charity box that reads: “Charity saves us from death.”

He also brings us Rogachov’s celebrations. In Wedding (1978), newlyweds stand under the shaky wooden entrance of their new house, another couple under a wedding canopy. The scene is surrounded by the people Kaplan remembers from his youth. Musicians on the rooftops of houses, people looking out of their windows – and goats, goats appear everywhere. In Poor Man (1978), Kaplan draws a town beggar as he trudges, a walking stick in his hand, through the town. He draws tailors, blacksmiths, millers, carpenters, watchmakers, organ grinders, all surrounded either by their tools, their town, or their children.

He draws his father, the town butcher, with a sign above that reads: “L. Kaplan’s Butcher Store”. He shows us babies gently being rocked to sleep by their mothers, young boys learning Jewish texts with their teachers, children dancing with the Torah, Purim celebrations, women lighting Shabbat candles, weddings, lovers, the head of a tallit-wrapped elderly Jew holding a book that has the word “Israel” on its cover, and different versions depicting a Jewishly garbed grandfather with his grandchild in a cap worn by Jewish children in the shtetls. For Kaplan, who had one sickly child, these drawings not only represent living memories of his own youth, but perhaps express his own desire of leaving a grandchild, even one birthed through drawing in his hand, as a legacy for himself – and for us.

Tanchum ben Levi Yitzchak and Sarah Kaplan died on July 3, 1980. He was buried in Leningrad, his tombstone designed by artist David Goberman, Kaplan’s friend. Goberman had sketched and photographed hundreds of Jewish tombstones in the towns that belonged to the Pale in the 1930s to the 1960s. Kaplan had used Goberman’s photographs to create his works of art, so Goberman’s design is symbolic. The top of the tombstone reads, in Yiddish: “The Artist Tanchum Kaplan 1902-1980.” The image of a goat, his most beloved animal that in many ways represents the world he never forgot, adorns the top of his matzevah.

Anatoly Kaplan lived through a most difficult time in Jewish history. Many of his friends suffered terribly and his beloved world of Rogachov was destroyed. Through his art, he preserved the precious Jewish world that would have been forgotten by the Soviet people. He was not only a “tormentor of stones” but also a “collector of stones”, gathering them and, in those dangerous times, offering a visual voice to a world that could have otherwise vanished forever.

Epilogue

This article took me a very long time to research and write. Since working on my PhD and book on the life of Isaac Babel back in 2005, I have not spent this much time on any writing. It took me some time to understand why.

As I read books and researched articles about Kaplan and his work, behind me stood my great-grandparents and other members of my family who were murdered in the Rogachov Ghetto. My grandfather who died right before we emigrated from Leningrad in 1978 stood by their side. The Jewish poets and writers who were murdered and disappeared in Soviet Russia were there as well. And, of course, Anatoly Kaplan looked down to see if my scribbles were at all capable of reflecting his life and the meaning he gave to his art.

The Soviet people were allowed one Jewish writer, Sholem Aleichem. They were permitted one Jewish artist, Anatoly Kaplan. The legacy that they – and so many others – have left us lives on in us and, hopefully, in our children.

It is to their memory that this article is dedicated.

עוד בבית אבי חי