Entrance, Abu Tor, Oil on Canvas, Dubi Shiff Art Collection - Tel Aviv, 130 * 98 cm

“It has been up to us to keep the world aglow.”

– James Hillman[1]

“We are bored in the city, there is no longer any Temple of the Sun.”

– Ivan Chtcheglov[2]

Among old electricity meters, through window bars shaped like crosses and flowers, in front of decorated tiles in doorways filled with light and dimness, Marek Yanai searches for the soul of the city. In the popular image of Jerusalem, the ancient city is a small space, defined and fenced, surrounded by the wall and divided into quarters. Outside lies the secular city. But Jerusalem can be perceived otherwise. The ancient city, holy Jerusalem, is reaching into the western side, beyond the walls. It is there, in various enclaves, apartments, gardens; in hidden yards, in the remains of a wall. Its antiquity might be independent of time, of the accumulating years. And in the walled city there are areas devoid of a past, hideously renovated. By “the ancient city” I refer to those places that kept their own pace for a period long enough to allow their spirit to be revealed, to become tangible. Like a tree needing time to reveal its glory, like a garment or a ceramic vessel that must be used for years before its beauty and character can be discovered, so does the city.

The true value of Jerusalem is embedded in those places. Looking for the sanctity of the city in its “holy places” is very much like looking for a person’s life in a single organ. Most of those places preceded the Israeli era. Built by Muslims, Armenians and Christians, more often than by Jews. And as can be seen in Yanai’s paintings, you wouldn’t discover them on tourists maps but rather in stairwells, old letter boxes, groves and people. No more than “trace elements”, those chemicals whose concentration in the body is very low (for example: zinc, iodine, chrome, copper) and are considered essential to its functioning. Like a biochemical process, without those places, Jerusalem would become just another giant city with a violent history. Those places, the places Marek Yanai is painting, give the city its sparks of life.

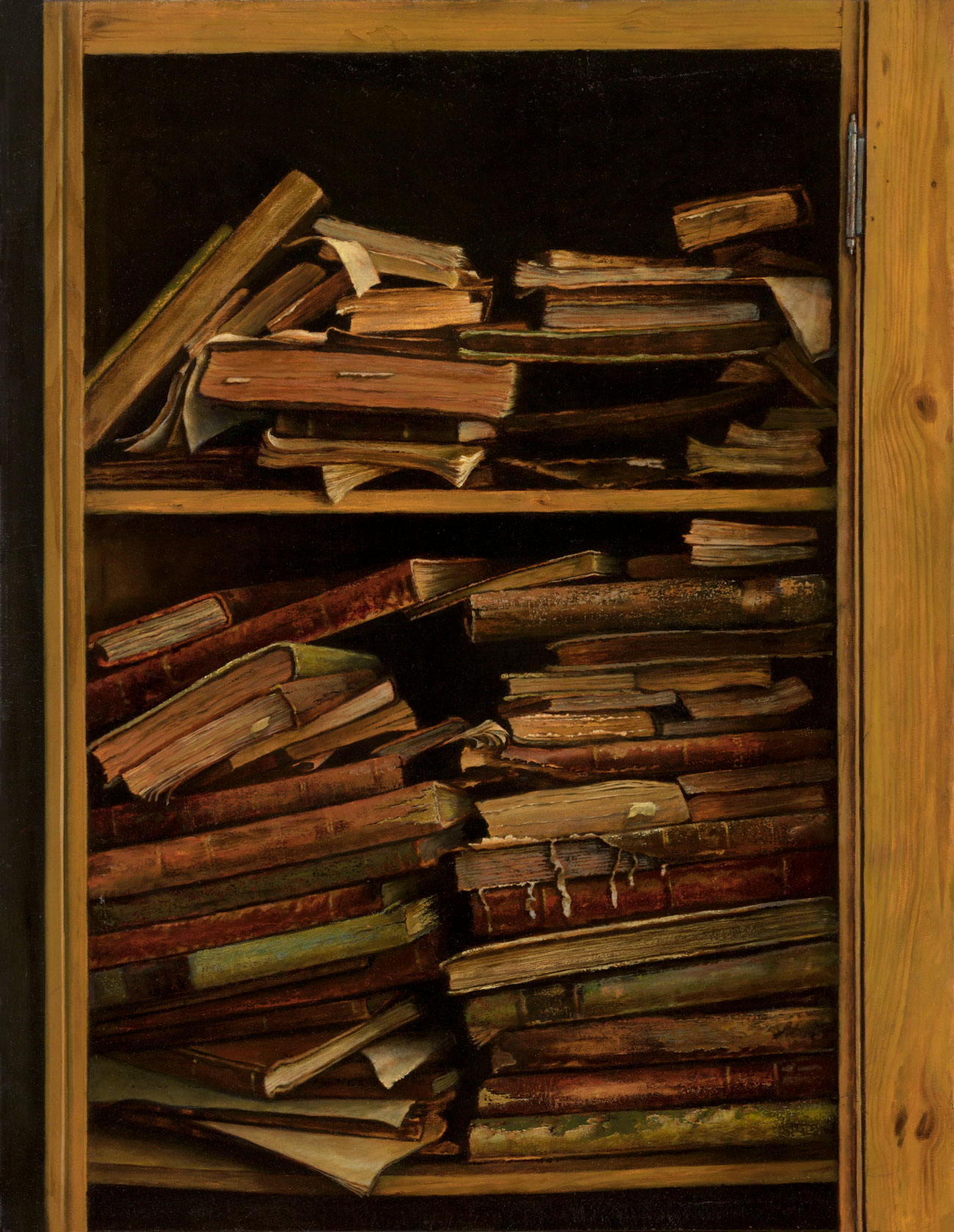

Genizah, Oil on Canvas, 90 * 70 cm|Marek Yanai

Entrance in Beit Lehem Road, Oil on Canvas, Dubi Shiff Art Collection - Tel Aviv, 146 * 130 cm| Marek Yanai

Yanai’s painting of indoor spaces demand the attention of all senses, not only vision. We need to sniff the old books, feel the texture of the pages turned by many hands and lines touched by many fingertips; let the skin feel the coolness and listen to the rustle of the shadow when entering, in a hot Jerusalem day, the thick walled stairwell, sitting in the covert of the cliff, finding solace in an unfamiliar house. The thickening shadow preserves a nighttime quality, and noon is quickly turning into sunset. In another painting we see a passage, a gate to the right and a private door to the left. In between, the painting offers a lull. An unseen tree is entering the space as if seeking a home, reaching forward with its shadow cast inside; opposite, the electricity meters and letterboxes focus on the outside world – letters, alternating current. How beautiful is their resemblance, declaring kinship of those in charge of bringing the external in. That is what this painting does. Look at the rectangle of light projected on the wall, the silhouette of a tree. The exterior (the sun, a tree) and interior (the wall) form a shape: the painter sees a letter sent from the world, receives it and delivers it to us.

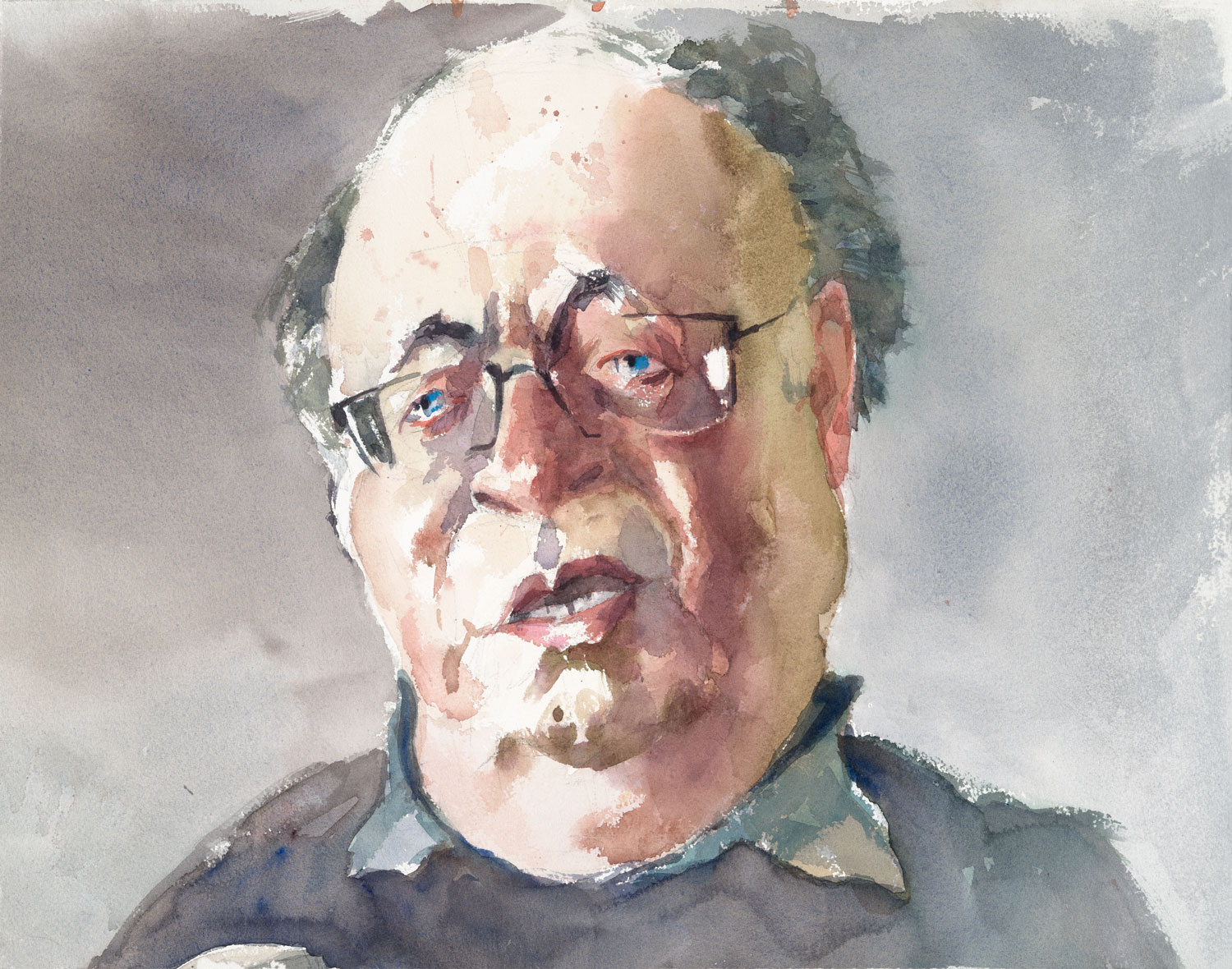

The artifacts of modernity too can have a soul. The letterbox (part of the communication network), the meters, an old Bakelite telephone, are not “antiques”. However, in these paintings they are already merged with deep time. They are not only a phenomenon of the present, but rather gradually emerging and being used, sometimes by more than one generation and thus temporally larger than us. A similar feeling is evoked by an ancient tree, planted before our grandparents were born, prior to the foundation of the city. It is humbling, not belittling. Your grandmother was chatting with her nana on this phone. Your uncle smoked this pipe before the great war, in countries you never visited. And you too can do the same. Here are a few lines from Elegy for the Departure of Pen, Ink and Lamp by Zbigniew Herbert (the Hebrew translation for this poem was made by David Weinfeld whose portrait was painted by Yanai, :

“Lightly we leave the gardens of childhood the gardens of things

scattering manuscripts oil lamps dignity and pens on our flight

[3]such is our deluded journey along the cliff side of nothingness”

David Weinfeld, Literary scholar, translator and Israeli literary editor, Watercolor on paper, 43.5 * 54.5 cm|Mrek Yanai

A strong air of elegy is present in Yanai’s paintings. Like us, he knows that these spaces of Jerusalem painted here, immersed in quietude, are threatened, about to be stormed by real-estate entrepreneurs and “market forces”, not knowing how long they would survive. More than replacing one way of lifestyle with another it is a possibility of a quiet and even holy presence in the city that is at stake.

Kiryat HaYovel, Oil on Canvas, 114 * 161 cm| Marek Yanai

An entrance in the German Colony #1, Oil on Canvas, 130 * 89 cm| Marek Yanai

An alternative Jerusalem can be seen in the painting of Kiryat Menachem housing projects, buildings that resemble a fortress’ wall or a giant tomb. This rigid, geometric symmetry of brutal rectangles is subverted again and again in Yanai’s paintings. His love for symmetry is apparent only when it’s broken – a symmetrical door would always have one wing open. It is essential, not only a matter of shapes: breaking the symmetry is an expression of vitality, of noticing the inimitable, rejecting the pompous and the monumental. The large ugly rectangles of Kiryat Menachem reflect an architectural indifference to the life of tenants, trying to reach an ideal and perfect shape that surprisingly cannot be beautiful, perfect and ideal but rather ugly and depressing. Yanai’s painting should be shown to architects, so they can get a sense of a good place to live in, so their building would fill a sensitive painter with joy. It is a simple question: can you imagine a painter painting happily in our contemporary stairwells? What can one paint there?

In other buildings that are meaningful for the artist, letters were shoved in and pulled out day in and day out – the relentless thuds of metal sheet frames, the curb stone sinking a little more each day when people are coming and going, now sunken under the open door. The electric current run through the wires and the meters sped up in winter, when the heater was turned on. Time and usage reveal the nature of things as well as their soul. Yanai’s soul was drawn to spaces created by men and women aware of such a possibility of space, place and things; artists who inhaled this space in their world and transferred it to others. It is a craftsmen’s world – makers of decorated tile, utensils, metalsmiths fashioning bars and doors. A decorated floor or window bar is no less valuable than a painting hung in the museum or on an apartment wall. Maybe even more so, because you see this floor you walk on every day, not only on special occasions. Walking on a flowery floor is meaningful, and so is a window bar communicating the language of plants. When Marek Yanai paints these spaces, he is seeking this sensitivity in the art world, in painting. Sensitivity that stems from touch and gentleness, not from intellectual ideas and trends.

So many contemporary artworks seem to be created by artists lacking the sense of touch, of smell, of taste and hearing (especially lacking the ability to hear silence) as if they had to make do with rational thought and an inspecting eye only. As if many artists are inspired today more by reading scholarly texts than by the texture of a round-flowery rug begging to be touched, to be sat on, a rug that warms your house in winter like a burning fire. Which can teach us more: reading critical essays in books or studying the unopened books about to be sent to the Genizah, with their bookmarks marking special paragraphs for a non-existing reader?

Mount Zion, View from Abu Tor, Oil on Canvas,

Private Collection - Jerusalem, 126 * 200 cm|Marek Yanai

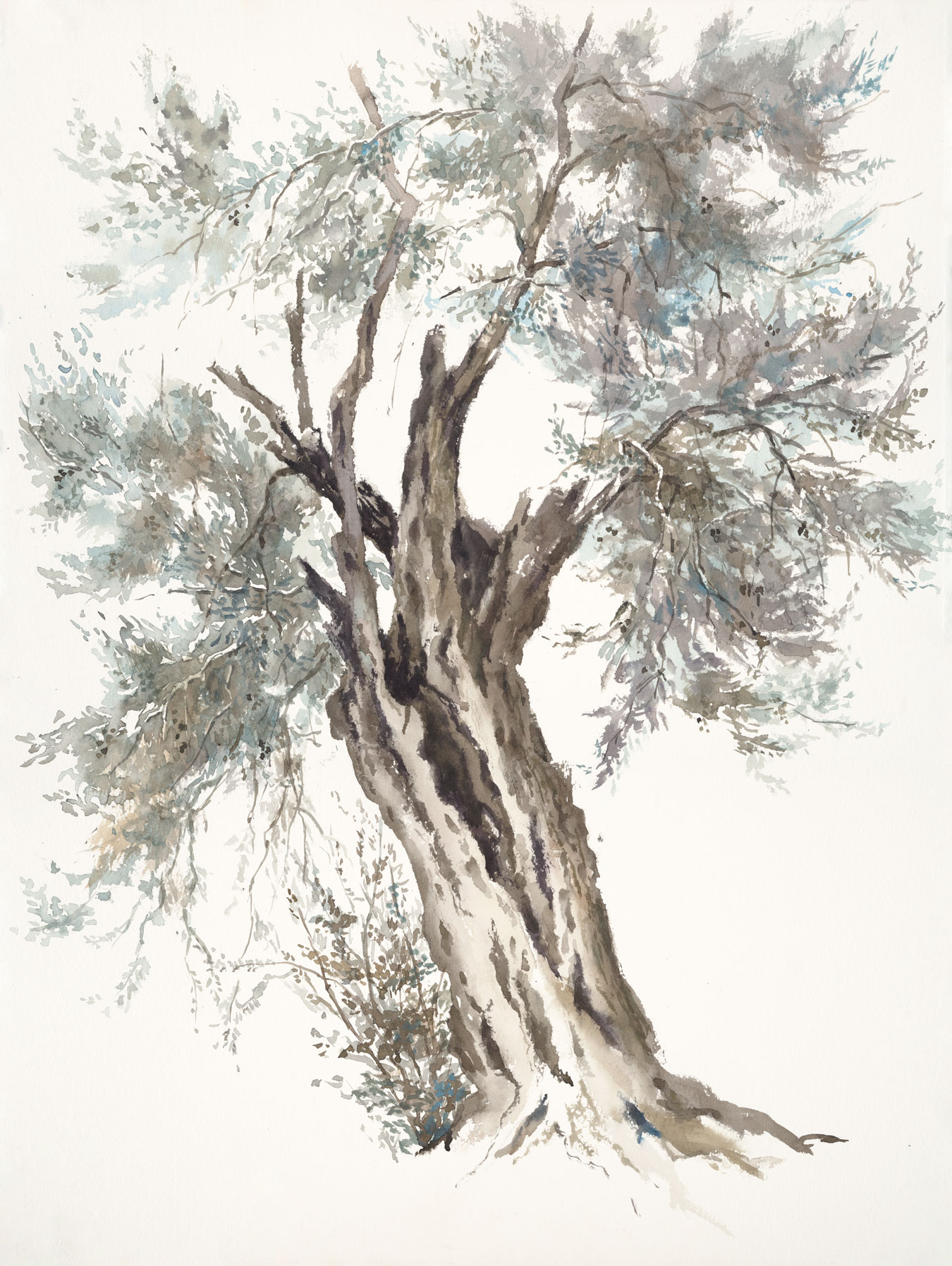

Portrait of an Olive Tree #1, Watercolor on paper, 76 * 57 cm| Marek Yanai

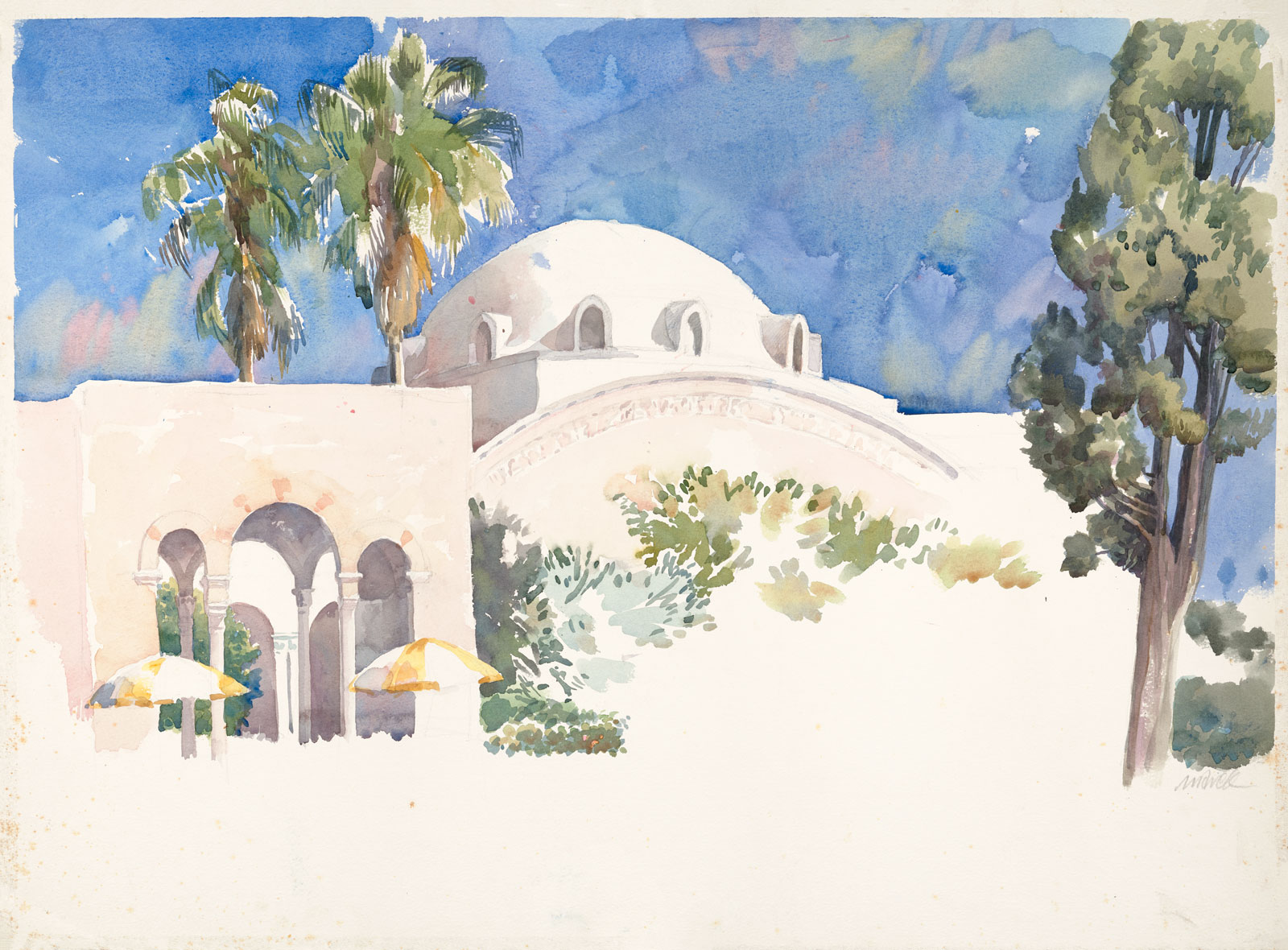

YMCA in White, Watercolor on paper, 55.5 * 75.5 cm|Marek Yanai

Alley in Ein Karem, Watercolor on paper, 55.5 * 76.5 cm| Mrek Yanai

Exploring Jerusalem’s views as painted by Marek Yanai reveals two forces: Lift and Depth. In one painting the cypresses burst from the roof like flames; another treefloats birdlike in the air, deprived of roots or soil. Other paintings convey a dialogue between past and present, dragging the city downwards, toward its past: the YMCA stone dome converses with the parasols, like a dinosaur chatting with the yellow birds who landed nearby for a split second; on Page 73 a house on the ground converses with another house, set inside a ditch. The city has at least two hidden sides in these paintings – one connected to the so called spiritual (the cypress’ "flame”) and one to its past and depth. In several paintings these aspects merge. For example, in the Genizah painting I mentioned that was created in the Beth Midrash in the Batei Rand neighborhood: the books are “vessels” containing the Holy Scriptures and thus spiritual; although as materials (old paper, binding glue) they are already part of the city’s geology, layered in their nook like soil.

Mood Board, Oil on Canvas, Dubi Shiff Art Collection - Tel Aviv, 70 * 100 cm|Marek Yanai

The depth of Jerusalem’s past is linked to a different past explored in Yanai’s paintings: the history of art. In one of his paintings, postcards of famous artworks (by Egon Schiele, Paul Klee, Leonid Balaklav, Ori Reisman and others) are arranged near simple vessels as if aspiring to become a Morandian still life.

In another work, a lemon in a breakfast scene is peeled into a twisted coil (absorbing sunlight, turning into a golden little sour sun on the table), an image prevalent in works by still life Dutch masters (Willem Kalf and others). Chardin is present here as well, in metal objects and smoking pipes. These are not direct quotes from other paintings but rather a sense that the life lived inside the domestic space is inspired by art from earlier periods. That Morandi’s light is kept aglow in the ordinary, even when it consists of a Formica dining table with a milk carton, a teapot, sweetener and salty pretzels. That one can sit in front of a breakfast scene and see a painting. Like this one.

Yanai’s portraits match the rest of the exhibition – both men and women depicted here – at least those whom I recognize – are part of the landscape, the place and therefore also of the city’s sanctity. The above-mentioned translation by David Weinfeld, poems by Hedva Harechavi and Yosel Bergner’s paintings – although he was not a Jerusalemite but could no doubt have become one (having lived in Safed for a while) – and others. These men and women build bridges between worlds, their hearts are filled with depth, imagination and dreams.

An entrance in Baka, Oil on Canvas, 130 * 98 cm| Marek Yanai

Marek Yanai’s doorways and stairwells are exactly that: places of stillness, imagination, silence, dreaming. No need to go to a hotel, even a café or a garden, to find such things: take your flask and find yourself a stairwell in Jerusalem that is not locked behind a buzzing intercom. Sit for a while on a half-lit half shadowed stair, see the light coming in, the colors of the letterboxes, each one of them unique, the magical map drawn on the tiled floor, see the door reflected in the floor as if it were a mirror, hear the wind in the pine trees and the birds stroked by wind. That is how you “keep the world aglow”: it is not an otherworldly mystical glow; not a glorious spectacle, just a simple shining floor, in the simple light, glowing as if covered by liquid light. Imagine the movement of evening newspapers and letters (so much paper, so many words!) in the letterboxes, waiting patiently like house gods, day after day, for the postmen’s message. Here one can sit and write the Odyssey. A poem, at least.

We (humans) create soul-filled places and they do the same for us in return. Then we respond with a poem or a painting and continue the conversation, amplify it, allow it to continue. I believe this is the subject and the effect of this exhibition.

Psychologist James Hillman (1926-2011), whose words I used as a motto, often wrote about the city and its soul as part of contemplating the ancient concept of The World’s Soul (anima mundi) and the ways in which it relates to the soul of the individual, who in our time frequently feels disconnected to the soul and more often than not denies its existence. One of his simple and beautiful suggestions is to think of the city as a place for lovers and try to imagine if people in love would like to walk its streets.[4] What do lovers want in a city? Shopping malls? Carparks? Huge theatres? multilevel intersections? Perhaps there are lovers who would love all that, but some would prefer to sit in the stairwells painted here, or in the small cafés, in the little bookshop, stroll the small alleys, sit quietly on a bench. You can still find such places in Jerusalem. For the world to have a soul, we need to grant it one. Only if we acknowledge the possibility of a soul-filled place, create it and imagine it as such, we would be able to have a space that has a soul.[5] Yanai’s paintings offer all that, especially those of indoor spaces, rooms and thresholds.

By contrast, if we define the world as “dead matter” or “just a background” we should not be surprised that architects and city planners create a meaningless, boring or even intimidating space. One in which pedestrians prefer to drown in their cellphone while walking. a different version of the world, examining it meticulously: which light penetrates such a place? What furniture would be in it? What kind of letterbox does it have? What sort of meaning do the dishes carry? Using the words of Japanese poet and philosopher Soetsu Yanagi (1889-1961), the dishes in Yanai’s paintings are “devoid of ambition”, objects that users “exchange a vow” with according to which “the more an object is used the more beautiful it will become, and the [6]more the user uses an object, the more that object will be loved”.

It’s not enough to build according to “spiritual” ideals, says Hillman. Imposing edifices like cathedrals, museums, monuments and temples alone would not allow the city to be soul-full and have a soul. Jerusalem has many such buildings – from the Great Synagogue to the Supreme court, from the Knesset to the Israel Museum, from the Bridge of Strings to the Hebrew University campus on Mount Scopus. Such buildings are also represented in Yanai’s landscapes; he acknowledges them but never paints their interiors. Unsurprisingly, the official Jerusalem remains in the background and unlike apartments and doorways, it does not reveal its intimate parts. In Hillman’s words, Marek Yanai’s paintings “enduring intimate conversation with matter”[7] particularly that of Jerusalem. Their direct simplicity is “raised to the level of the ordinary”[8] and thus they are useful. They show us what is left of Jerusalem’s soul, it's important uniqueness – they point out the direction we shouldn’t steer it, and the appropriate scale the city should have.

[1] James Hillman, City & Soul (Uniform Edition of the Writings of JH, vol. 2), Spring Publications 2018, p. 43

[2] Ivan Chtcheglov, Formulary for a New Urbanism, Situationist International Anthology,

Revised and Expanded Edition, Edited and translated by Ken Knabb, Bureau of Public Secrets, 2006

[3] Translated by Alissa Valle, http://www.divasofverse.com

[4] James Hillman, City & Soul (Uniform Edition of the Writings of JH, vol. 2), Spring Publications 2018, p. 25

[5] James Hillman, City & Soul (Uniform Edition of the Writings of JH, vol. 2), Spring Publications 2018, p. 29

[6] Soetsu Yanagi, The Beauty of Everyday Things, trans. Michael Brase, Penguin 2017, pp. 36-38.

Soetsu Yanagi, The Beauty of Everyday Things, trans. Michael Brase, Penguin 2017, pp. 36-38.

[7] James Hillman, City & Soul (Uniform Edition of the Writings of JH, vol. 2), Spring Publications

[8] Soetsu Yanagi, The Beauty of Everyday Things, trans. Michael Brase, Penguin 2017, p. 22.

עוד בבית אבי חי