The Torah regulates slavery rather than abolishing it. But reading Rashi’s medieval commentary reveals a remarkable interpretive effort to humanize the text

Parashat Mishpatim opens with the laws of the Hebrew slave. From today’s perspective, the fact that the Torah regulates slavery rather than abolishing it entirely is disappointing. But this is moral anachronism. By ancient standards, regulating slavery and claiming that slaves have rights was revolutionary.

Reading the verses alongside Rashi’s XI-century commentary – heavily influenced by the Oral Torah – reveals an attempt to reshape the text.

Who Goes Free?

“When you acquire a male Hebrew slave, he shall serve six years; in the seventh year he shall go free, without payment.” (Exodus 21:2)

There were two ways to acquire a Hebrew slave: when someone in financial distress sold himself into slavery, or when the court sentenced someone who stole to slavery for restitution. Who goes free in the seventh year without payment? Since the verse says “when you acquire,” and since there’s dramatic improvement here, it seems reasonable to think this refers to one who sold himself. Yet Rashi says the opposite – this also refers to one sold by the court. Every Hebrew slave is entitled to freedom without payment in the seventh year.

“He shall leave alone”

The Torah continues: “If he came single, he shall leave single; if he had a wife, his wife shall leave with him. If his master gave him a wife, and she has borne him children, the wife and her children shall belong to the master, and he shall leave alone” (ibid., 3-4).

There is a distinction between the slave’s wife from before slavery and a woman the master “gives him.” In those days, a master could increase the number of his slaves by having his male and female slaves enter relations – the children would belong to him. If you came unmarried, the Torah says, you cannot marry during slavery. “He shall leave alone.” And regarding a female slave the master gives you, when you go free in the seventh year, the woman and your children will remain behind.

What does Rashi change? He says if the slave arrives unmarried, the master is forbidden to give him a female slave to bear children from him. It’s inconceivable that a person’s first and only children would not be his. “If his master gave him a wife” refers, according to Rashi, only to someone sold into slavery when already married with children. Perhaps then he could cope psychologically with the master giving him an additional wife who bears him additional children.

And “his wife shall leave with him”? This seems obvious since she wasn’t sold, so what does this mean? Rashi teaches that the master is obligated to provide for and feed the slave’s wife and children during slavery. When the slave leaves, this obligation ends.

Symbolic deterrence and rebuke

“But if the slave declares, ‘I love my master, and my wife and children: I do not wish to go free,’ then his master shall bring him to the judges; he shall also bring him to the door, or to the door post; and his master shall bore his ear through with an awl; and he shall serve him for ever.” (ibid., 5-6)

Bring him before God? Rashi explains this means the judges, the court that sold the slave initially. One must return to them before the ceremony – a protective measure for the slave.

Why pierce his ear? Rashi quotes the midrash: “That ear which heard on Mount Sinai what I said, ‘For unto Me the children Israel are servants’ and yet its owner went and procured for himself another master – let it be pierced!”

The ceremony is symbolic deterrence and rebuke. The Torah encourages the slave to be freed and conveys the message: slavery is bad.

“He shall serve him for ever”? Here interpretive audacity reaches its peak. Rashi writes: “Until the Jubilee.” A Hebrew slave will never serve forever. In the Jubilee year, the year of liberty and freedom, he will be freed.

Humanizing Ancient Texts

The profound changes Rashi and other commentators introduced to these verses reveal their deep discomfort with slavery. Before us is a remarkable interpretive effort to humanize the text without completely nullifying it. This effort often characterizes the Oral Torah – perhaps this is one of interpretation’s most important roles: to humanize ancient texts in accordance with each generation’s developing moral perspective.

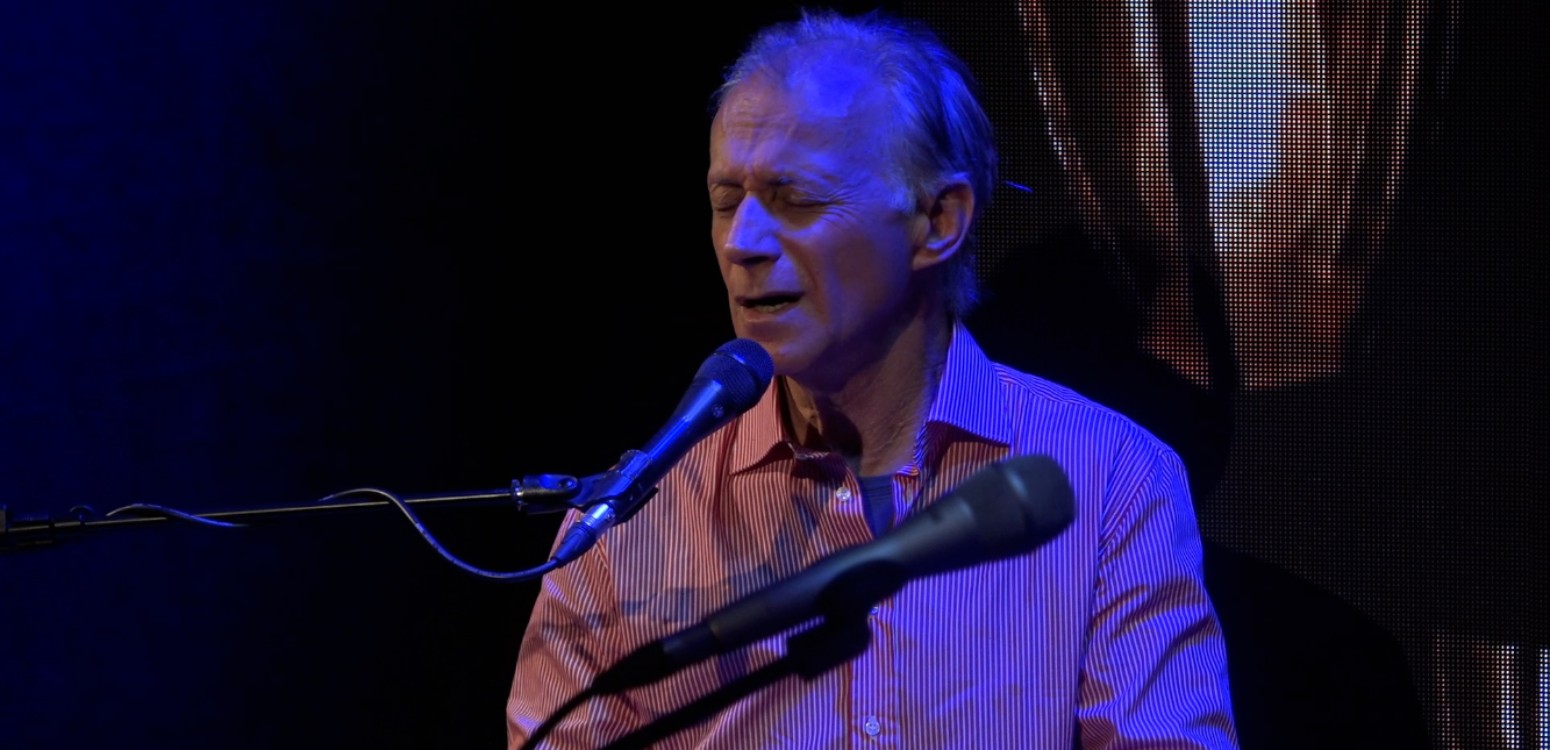

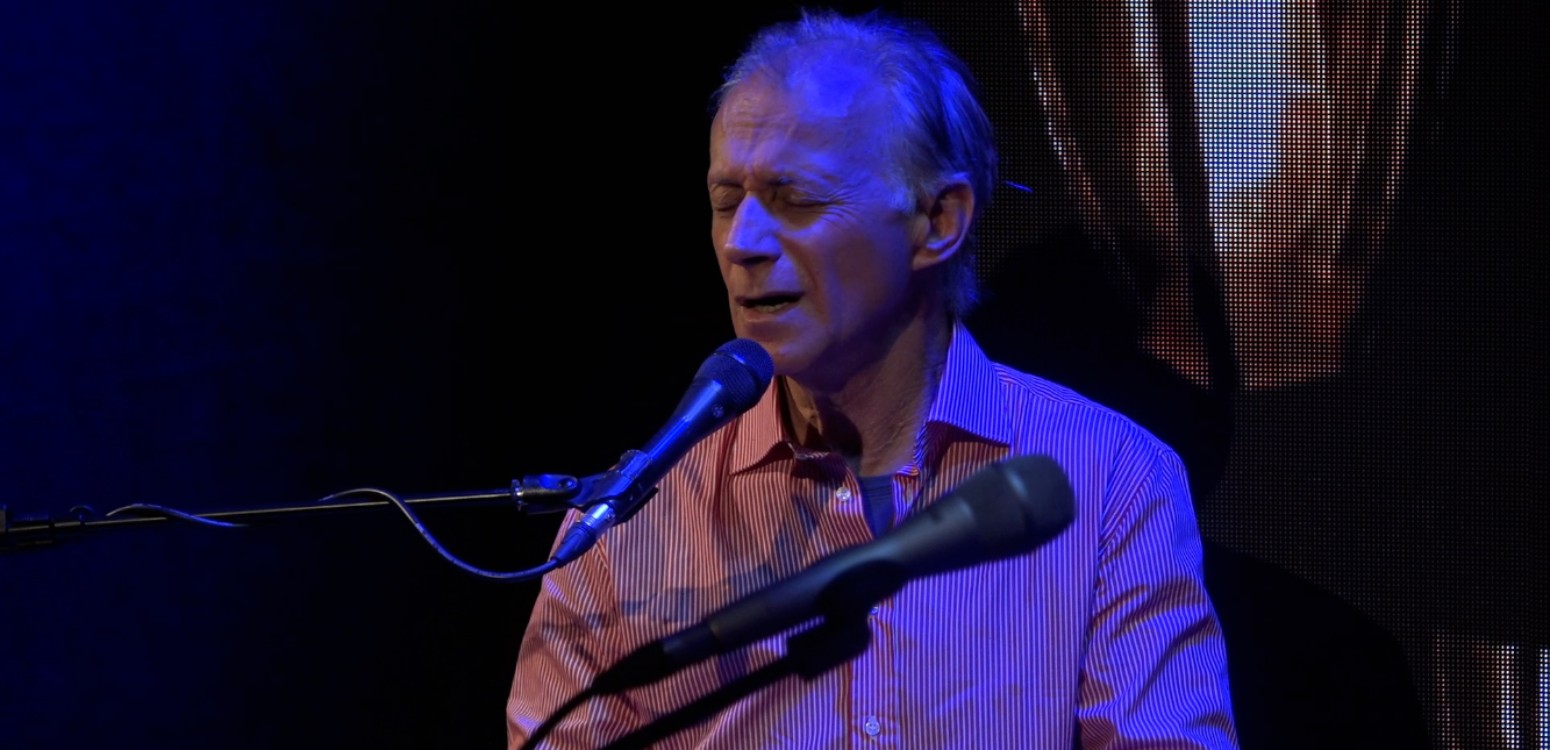

Lior Tal Sadeh is an educator, writer, and author of “What Is Above, What Is Below” (Carmel, 2022). He hosts the daily “Source of Inspiration” podcast, produced by Beit Avi Chai.

For more insights into Parashat Mishpatim, listen to “Source of Inspiration”.

Translation of most Hebrew texts sourced from Sefaria.org

Main Photo: The Covenant Confirmed, by John Steeple Davis (1844-1917), as in Exodus 24.\ Wikipedia

Also at Beit Avi Chai