Should the Torah legislate our feelings? The prohibition against coveting raises fundamental questions about action versus desire, consent versus willingness, and about the kind of culture we want to create

There are 365 negative commandments in the Torah. Even the brief Ten Commandments contain a packed list of prohibitions: “You shall have no other gods besides Me”; “You shall not make for yourself a sculptured image, or any likeness”; “You shall not bow down to them or serve them”; “You shall not take the name of the Lord your God in vain”; on the Sabbath, “you shall not do any work””; and of course “You shall not murder. You shall not commit adultery. You shall not steal. You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor” (Exodus 20:2-12).

These verses instruct what not to do. But then comes the tenth commandment, which departs from the realm of action and addresses our inner life: “You shall not covet your neighbor’s house: you shall not covet your neighbor’s wife, or male or female slave, or ox or ass, or anything that is your neighbor’s” (ibid., 13). This command regarding our feelings seems strange. Should the boundaries of permitted and forbidden really penetrate our souls?

Action or Feeling?

Many commentators say no. They argue the prohibition is meant to prevent action – if you don’t allow yourself to covet, you won’t reach the point of acting on it. It’s arrogant to think you can give free rein to problematic desires throughout life and never act on them.

But other commentators argue that coveting itself is a moral problem, even without action. The longing for what belongs to someone else indicates a spiritual flaw. What happens inside us is central to who we are, and we should work to control our thoughts and feelings.

The Heart of the Matter

This idea is reminiscent of one of the Four Noble Truths in Buddhism, which sees craving and aversion as the source of suffering. The very yearning for objects of desire is already suffering. The task becomes not just “don’t covet your neighbor’s possessions,” but abandon craving altogether.

The New Testament takes this further. In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus teaches that looking at a woman with lust is already committing adultery in the heart. Coveting itself, and not just the act, constitutes the transgression.

Consent Is Not Enough

Maimonides in his Mishneh Torah offers a fascinating perspective. He defines an act of coveting as follows: “Anyone who covets a servant, a maidservant, a house or utensils that belong to a colleague, or any other article that he can purchase from him and pressures him with friends and requests until he agrees to sell it to him, violates a negative commandment, even though he pays much money for it, as Exodus 20:14 states: ‘You shall not covet.’ The violation of this commandment is not punished by lashes” (“Laws of Robbery and Lost Property,” Chapter 1, Law 9).

Here Maimonides touches on the crucial distinction between consenting and willing. Sometimes we consent to please our friends without truly wanting to do what they are asking us to do. Consent has tremendous importance – it distinguishes robbery from legal exchange, rape from acceptable relationships. But consent is not everything. It doesn’t indicate the health of a relationship, nor does it guarantee consideration, love, or friendship. In good relationships, we aspire to mutual desire, not just the low bar of consent.

This is the depth of “You shall not covet” according to Maimonides: don’t pressure your friend until they consent to give or sell you what is theirs. It’s not robbery, there’s no flogging, but it is the root of alienation and lack of caring.

We all covet from time to time – let’s not be too moralistic about it. But gathering these interpretations, we discover the tenth commandment contains an attempt to create a culture worth living in: a culture where people can be content with their lot; a culture not based on infinite acquisitive appetite; a culture whose core is love, not alienation.

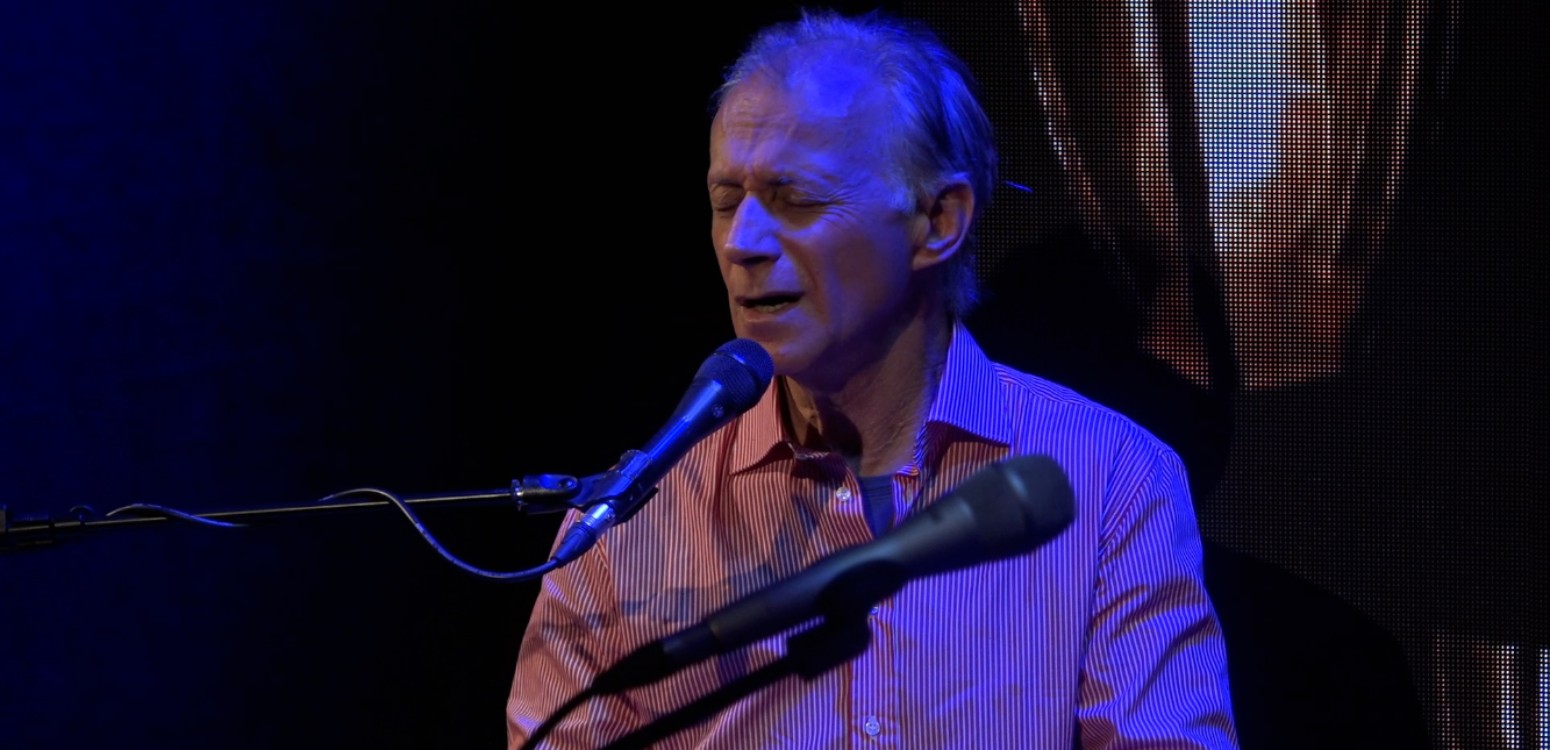

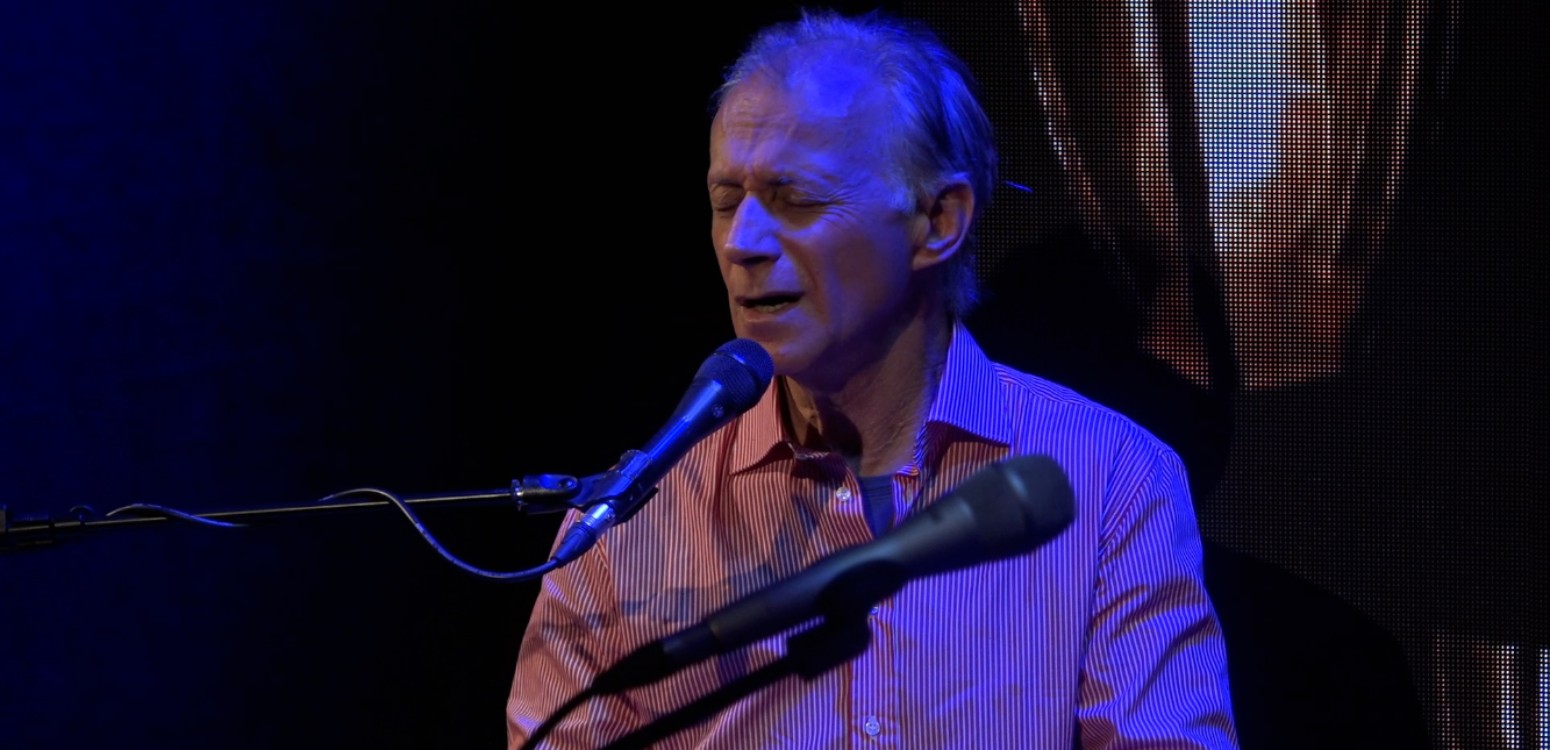

Lior Tal Sadeh is an educator, writer, and author of “What Is Above, What Is Below” (Carmel, 2022). He hosts the daily “Source of Inspiration” podcast, produced by Beit Avi Chai.

For more insights into Parashat Yitro, listen to “Source of Inspiration”

Translation of most Hebrew texts sourced from Sefaria.org

Main Photo: Jethro and Moses, as in Exodus 18, watercolor by James Tissot\ Wikikpedia

Also at Beit Avi Chai