Early Zionist thinkers grappled with profound questions of belonging: Were Jews Western or Eastern? Dr. Hanan Harif explores forgotten debates about Jewish-Arab kinship and Middle Eastern identity that shaped – and still challenge – Israeli consciousness

When European Zionists first arrived in Palestine, they were disappointed to experience a feeling of foreignness. The land they called their ancestral homeland felt alien, its Arabic-speaking inhabitants unfamiliar, its climate and customs strange. For Dr. Hanan Harif, lecturer at the Tel-Hai Academic College (soon to be a university) the question of how early Zionists grappled with their place in the Middle East remains one of the movement’s most fascinating and unresolved puzzles.

“From the moment they set foot on the land – and sometimes even before – European Zionists had to overcome a sense of foreignness that arose when they were confronted with the reality of the Land of Israel,” Harif explains. This wasn’t merely a matter of adjustment and acclimatization but touched on fundamental questions of identity: Were the Jews a Western or Eastern people? Were they European or Middle Eastern? And was Zionism a part of Western Colonialism or rather an anti-colonial movement? These questions were fiercely debated.

We don’t belong in Europe

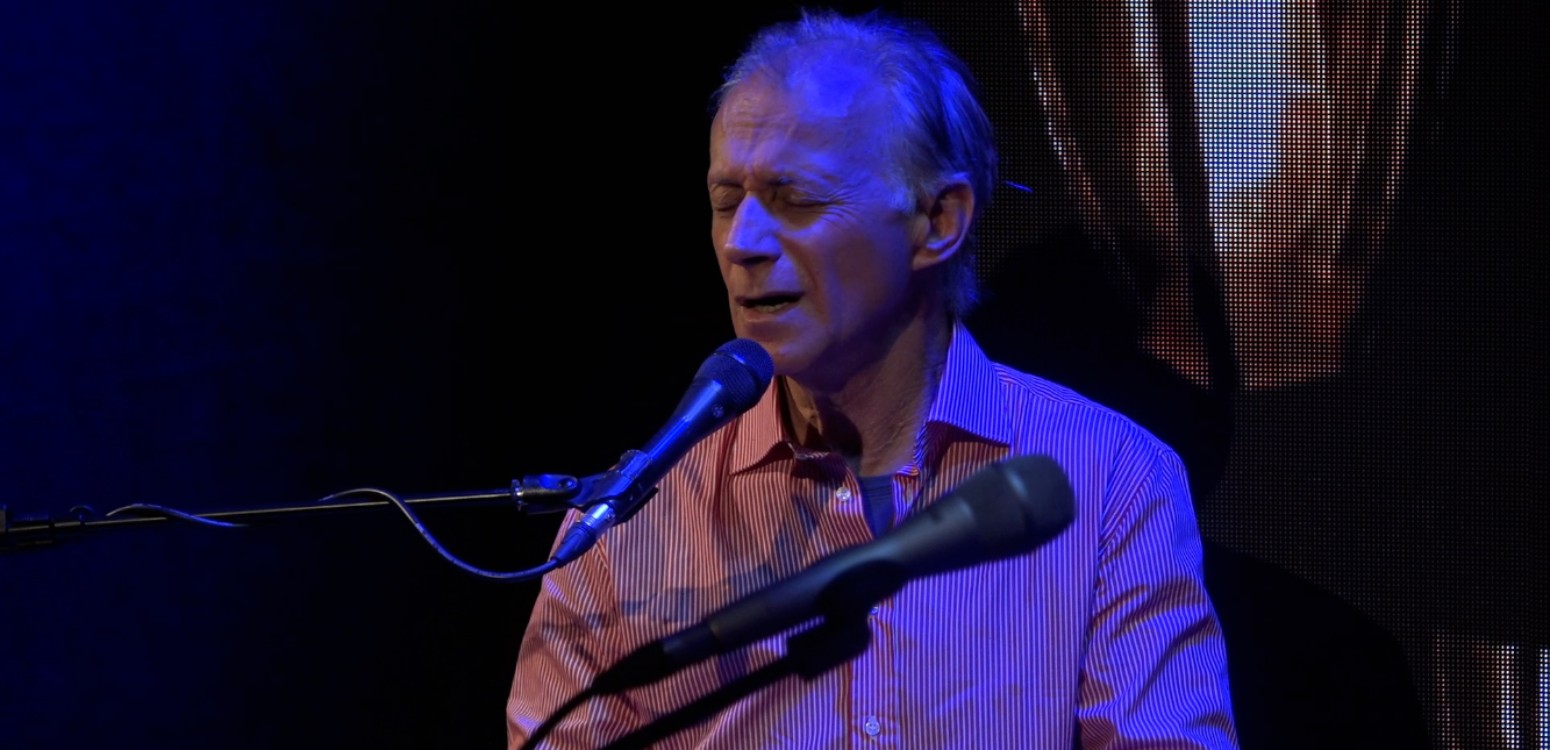

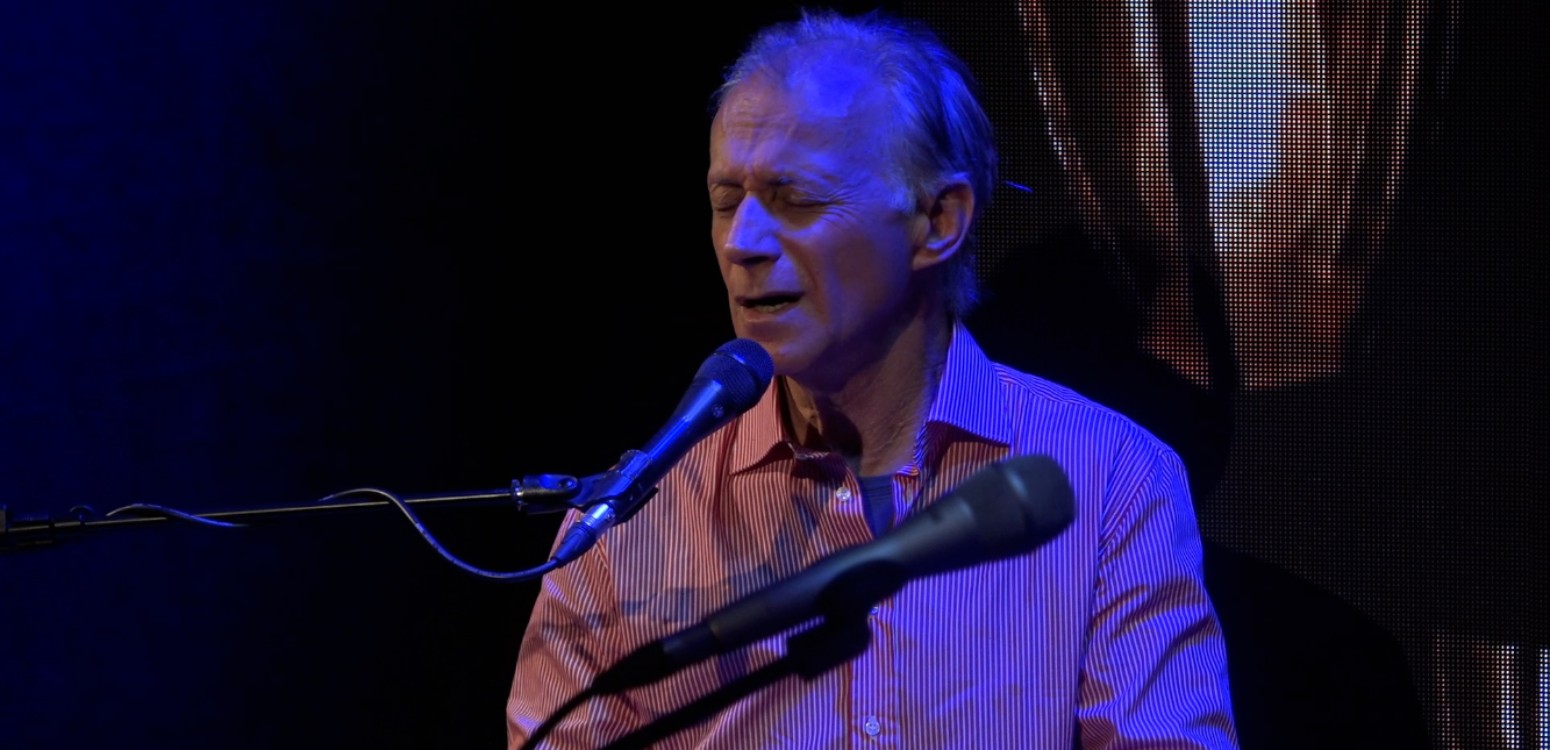

Harif, whose lecture series at Beit Avi Chai explores this topic, specializes in the history of Jewish culture in the age of nationalism, focusing on the encounter between West and East. His 2019 book “For We Be Brethren: The Turn to the East in Zionist Thought” examines figures and ideas that were almost forgotten once Israel achieved independence but in recent years have experienced a surprising revival.

The story begins with rejection. Early Zionist thinkers like Moshe Leib Lilienblum (1843–1910) felt profoundly unwelcome in European society. “Lilienblum and other early Zionist thinkers internalized the antisemitic notion regarding the Jews – we are Semites, foreigners, we do not belong here,” Harif notes. The sense of being rejected was dominant in early Zionist writing

An outpost of civilization against barbarism

This rejection at the hands of Europe, though, didn’t lead to an immediate embrace of Middle Eastern identity. Theodor Herzl (1860–1904) declared that the Jewish state would be an “outpost of civilization against barbarism,” insisting on a distinctly European orientation. Yet other voices emerged, seeing Zionism instead as part of a broader awakening of the East. These thinkers wanted Zionism to collaborate with anti-colonial movements, including those of the Arabs. Early Zionist writers like Yehuda Leib Levin (1844–1925), Mordechai Ze’ev Feierberg (1874–1899), Moshe Eizman (1847–1893) and a few others viewed Jewish national revival through this lens of regional awakening.

One of the most surprising strategies for overcoming foreignness emerged in what Harif calls the “origin of the fellahin debate.” This discussion, which engaged prominent Zionist thinkers like Ber Borochov (1881–1917), David Ben-Gurion (1886–1973), and Yitzhak Ben-Zvi (1884–1963), centered on the provocative claim that the Arab peasants of Palestine were actually descendants of the ancient Jews who had remained on the land since the destruction of the Second Temple.

“As part of the search for a connection to the Land of Israel and in an attempt to overcome the sense of foreignness, they explored the Jewish origins of the Arab fellahin,” Harif explains. According to this logic, if the fellahin were descended from ancient Jews, then both groups shared deep roots in the land, and Jewish immigration represented not invasion but reunion. This also offered a way to imagine coexistence and shared belonging. If both Jews and Arabs were children of the same ancient Israelite population, their relationship could be reimagined as fraternal rather than colonial.

Thoughts on Pan-Semitism

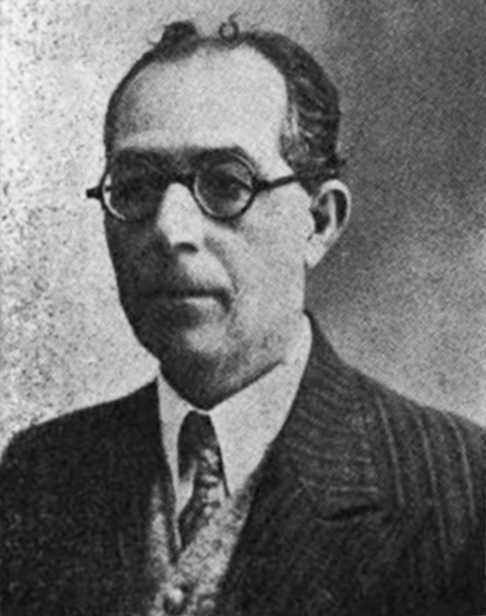

Among the figures that fascinate Harif are Rabbi Binyamin (1880-1957) and Nissim Malul (1892–1959). Born in Galicia in 1880, Rabbi Binyamin (pseudonym of Yehoshua Radler-Feldman) was a writer, translator, prolific columnist and editor and a key figure among the Second Aliyah intellectuals. He developed the idea of “Pan-Semitism,” arguing for an essential connection between Jews and Arabs as two ancient, Semitic peoples. “This wasn’t a belief in racial pseudoscience,” Harif emphasizes. Rather, it was an adoption of racial terminology (“Semites”) as an ideological tool to promote cultural and linguistic proximity and to encourage cooperation and further mutual understanding between Jews and Arabs in the land of Israel.

Rabbi Binyamin went further, stressing the religious dimensions of Pan-Semitism. He argued that Judaism and Islam were closer to one another than Christianity: a common theological claim to which he attached significant political implications. For him, as for some other thinkers, the religious proximities bared a potential to bridge over political tensions. Religion, in other words, was not the problem but was a part of the solution. This idea was later echoed by thinkers who promoted inter-religious discourse as means to overcoming political conflicts.

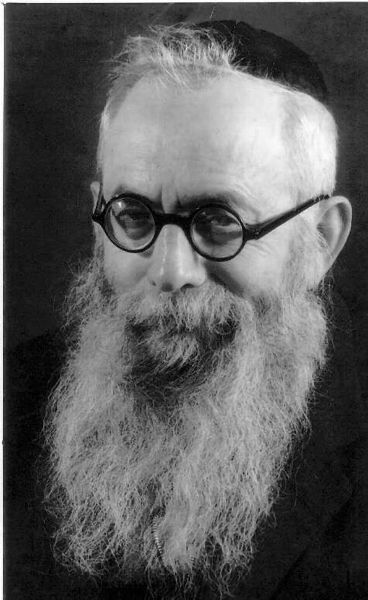

The Safed-born Nissim Malul, a playwright, translator and journalist who (like Rabbi Binyamin) worked for Arthur Ruppin (1876–1943) at the Palestine Office of the Zionist Organization, brought a somewhat different perspective. An Arab-speaking Jew born in the Land of Israel, he shared similar ideas about Arab culture and Jewish-Arab affinity but, unlike most European Zionists, had a deep, intimate connection to the Arab culture himself. Malul headed the Department of Arab Press of the Palestine Office which made him intimately familiar with Arab discourse and concerns. Malul, who served Zionist interests for many years through his wide connections in the Arab world, also urged European Jews to better understand their new home, to study Arabic, and to take part in the Arab culture.

In search of localism

According to Harif, these and related strands of thought represent a search for meqomiyut – localism or place-rootedness, a notion that was demonstrated vividly though somewhat artificially by members of HaShomer, the early Zionist defense organization, who adopted Arab vocabulary and dress and aspired to imitate the Bedouins. They quite literally “went native,” or at least tried to, performing an image that bridged their European origins and their Middle Eastern present. However, Harif states, the Zionist grappling with the East and the Arab region was much broader and more complicated than that.

What most surprised Harif in his research was how central these debates once were to Zionist discourse. “In the beginning I was surprised by virtually everything because it was all new to me,” he admits. “These ideas were very well known and there were heated debates around them. But I – like most other Israelis – had never heard of them.” The amnesia was nearly complete. Ideas that had been integral to Hebrew and Zionist culture, that had generated passionate arguments and inspired practical experiments, had simply vanished from collective memory.

“After 1948, much of this debate was forgotten,” Harif explains. The dominant narrative emphasized Israel’s Western orientation, its democracy, its technological advancement – all coded as European values. The idea that Israel might fundamentally belong to the Middle East, that Jews might regard themselves as ‘Semites’ with more in common with Arabs than with Europeans, faded into obscurity.

Questions that remain unresolved

In recent years, though, there has been a revival of interest in these ideas, extending beyond the academic world. “This is in part because of the feeling that Zionism needs to broaden its scope and new ideas are needed,” Harif says. In fact, Israel could not possibly remain alienated to the Middle East due to the large number of Mizrahi Jews who immigrated during the 1950s–1960s. However, it took decades until these aspects of pre-state Zionist discourse reentered historical research. When he began working on the topic fifteen years ago, Harif felt quite alone. Now it’s much more popular, both in universities and among the general public.

The thinkers Harif studies struggled with questions that remain unresolved. Whether their vision was naïve, whether it could have succeeded, whether it’s still relevant – these questions drive Harif’s research. The foreignness that early Zionists felt hasn’t entirely disappeared, but neither has the impulse to overcome it. The questions that obsessed the likes of Rabbi Binyamin and Nissim Malul – to mention only two out of many – continue to shape and challenge Israeli identity today.

Also at Beit Avi Chai