The same reality can be seen as tragedy or providence, depending on how we frame it. Joseph’s reconciliation with his brothers reveals how reframing doesn’t just provide comfort – it’s a tool that shapes our experience and choices

The same event can be seen as a tragedy or a miracle, a failure or a lesson, depending entirely on how you frame it. This isn’t just philosophical wordplay – it’s one of the most powerful tools we have for navigating life.

Early in my infantry training, the unit doctor deemed me unfit for combat duty – too thin, he said. A few days later, my commander asked me a simple question: “If you had to walk twenty kilometers into the desert right now, could you do it?” I said I probably could not. “And if someone’s life depended on it?” Then yes, I told him. “That’s why you’re here,” he said.

The medical tests came back normal and I stayed. But what stuck with me was how a single conversation shifted my entire perspective – from “I can’t do this” to “I can do what matters.” That shift is called reframing.

Framing is the lens through which we view reality. We rarely notice how much it shapes our perception, assuming that reality dictates how we see things. Often it’s the reverse: how we choose to see things shapes our reality. This fact has been proven in recent decades through a series of studies in behavioral psychology.

Joseph saw it differently

One example of framing and reframing in the Torah is found in this week’s parashah. Joseph’s brothers carry intense guilt over what they’ve done to him. They threw their younger brother into a pit and sold him into slavery. He’s probably dead, or at best living in bondage. They committed a terrible crime and turned their father into a bereaved parent who has mourned for over twenty years. This story matches the facts as they happened. We, the readers, know it too. But Joseph, the victim of this story, reframes it entirely.

“Then Joseph said to his brothers, ‘Come forward to me.’ And when they came forward, he said, ‘I am your brother Joseph, he whom you sold into Egypt. Now, do not be distressed or reproach yourselves because you sold me hither; it was to save life that God sent me ahead of you. It is now two years that there has been famine in the land, and there are still five years to come in which there shall be no yield from tilling. God has sent me ahead of you to ensure your survival on earth, and to save your lives in an extraordinary deliverance. So, it was not you who sent me here, but God—who has made me a father to Pharaoh, lord of all his household, and ruler over the whole land of Egypt.’” (Genesis 45:4-8)

Two completely different stories

From the brothers’ point of view, they are criminals who chose through free will to abuse their younger brother and betray their father. From Joseph’s point of view, they are messengers in a divine plan – a chain of events that placed him in Egypt to save nations from famine. The same reality, two completely different stories.

Framing shapes our consciousness, yet we can’t perceive reality without it. Understanding that we often react to our framing rather than to reality itself should prompt us to pause and ask: is there another way to see this? Can I tell myself the same story differently? This isn’t just psychological comfort – it’s a tool for how we experience the world and make decisions. Joseph chose reframing, and instead of becoming bitter and vengeful, he became someone who cared for his family and saved the people of Israel.

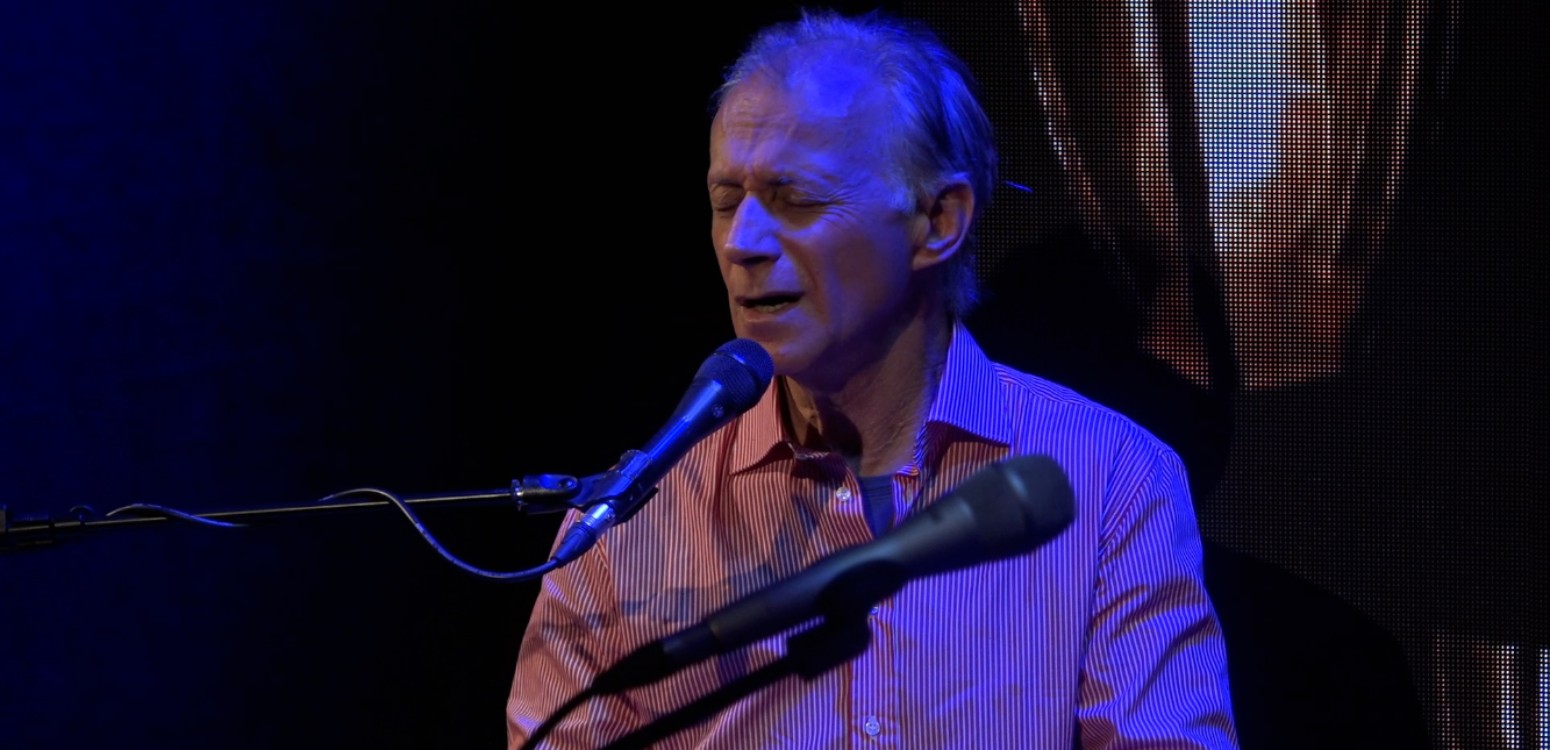

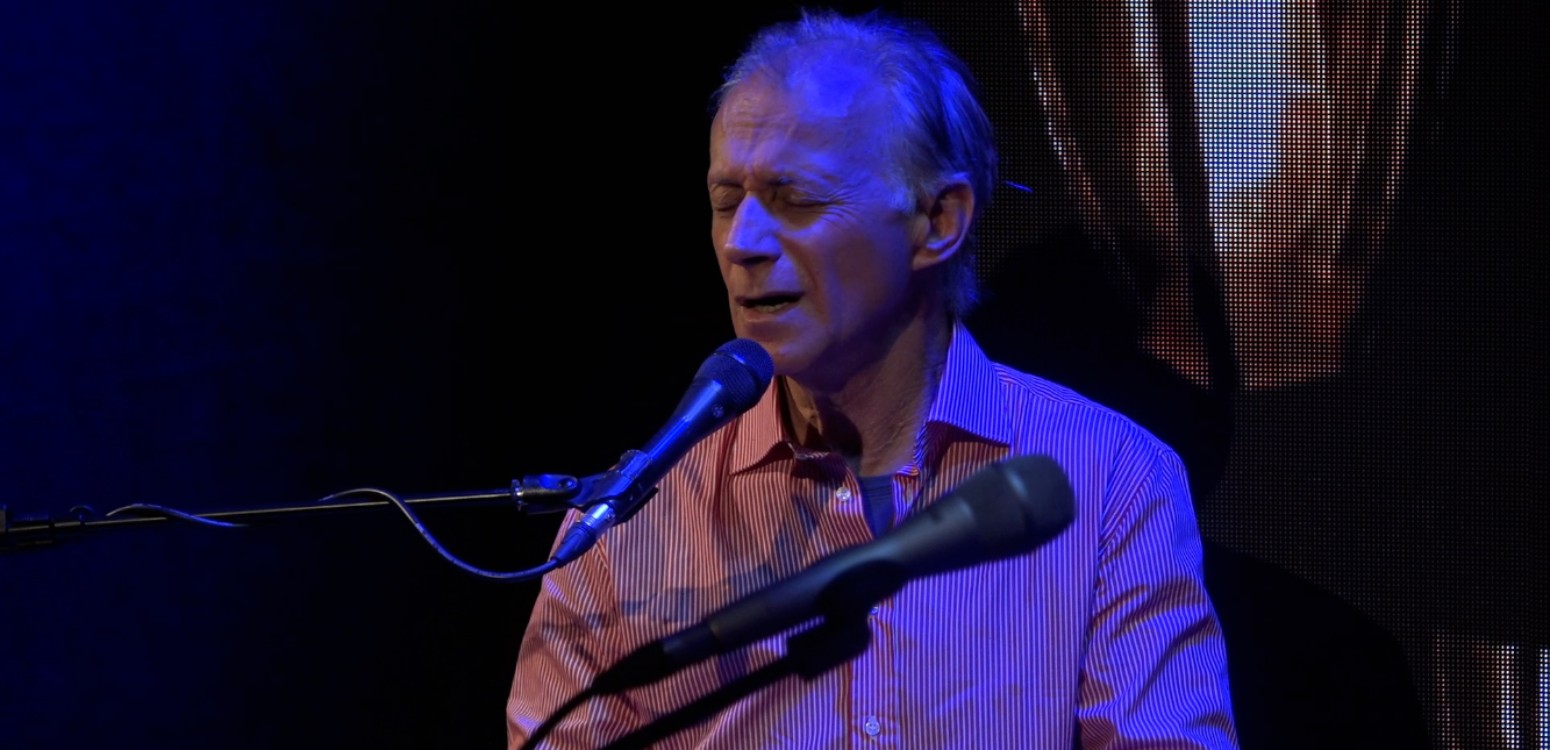

Lior Tal Sadeh is an educator, writer, and author of “What Is Above, What Is Below” (Carmel, 2022). He hosts the daily “Source of Inspiration” podcast, produced by Beit Avi Chai.

For more insights into Parashat Vayigash, listen to “Source of Inspiration”.

Translation of most Hebrew texts sourced from Sefaria.org

Main Photo: "Joseph Makes Himself Known to His Brethren", a Bible illustration by Gustave Doré\ Wikipedia

Also at Beit Avi Chai